Intermodal: Too Much of a Good Thing?

The growing popularity of intermodal transportation leaves more shippers planning their way around equipment shortages and traffic jams.

Intermodal transportation is a big deal, and it’s steadily getting bigger. The numbers bear that out. Rail intermodal loadings posted year-over-year gains for 56 months in a row, reported the Association of American Railroads (AAR) in July 2014. Ocean containers also fuel the intermodal boom. For example, the National Retail Federation (NRF) predicted in August 2014 that import volumes at U.S. ports covered by its Global Tracker report would reach the highest level ever recorded for one month since the NRF launched the Tracker in 2000. Much of that container traffic moves to and from seaports on intermodal chassis hauled by drayage trucks, or else it gets loaded directly onto trains.

Intermodal has gained a reputation as a reliable and economical transportation option. But this strategy also poses serious challenges, largely due to the growing number of containers in the ports, on the rails, and on the road. The more shippers embrace intermodal, the more daunting those challenges become.

Demand for intermodal transportation is exerting uncomfortable pressure in several ways. Congestion in seaports and on surrounding highways, a shortage of locomotives and crews on freight railroads, competition with conventional freight for space on the rails, the ongoing truck driver shortage, and a major shift in the market for ocean chassis—taken together, they’ve created a serious intermodal capacity crunch.

Trucks Crowd the Ports

That capacity challenge is easy to observe in many U.S. seaports, where heavy container traffic plus inadequate infrastructure produce frequent gridlock. "All that volume results in double the number of trucks trying to get containers in and out of the ports," says Michael Smith, president of ASF International, a drayage company based in Mobile, Ala.

One cause of overcrowding is the race to build bigger container vessels. "It seems like new records are broken every day in the size of ships deployed in world markets," notes Aaron Ellis, public affairs director at the American Association of Port Authorities, Alexandria, Va. "When these ships come in loaded with increasingly more containers, they have to be unloaded and moved off-terminal faster."

With deeper seaports than in North America, Europe has already embraced "mega-vessels," says Robert Burdette, vice president, strategic development at Baltimore-based logistics company Shapiro. Ships slightly smaller than "mega" now call on U.S. ports, and when the project to widen the Panama Canal is complete, we’re bound to see more of them, he says.

As those larger vessels disgorge more boxes, terminal operators have been cutting the number of days a shipper can keep a container on site before incurring a demurrage charge.

"Now add the chassis nightmare, where truckers are driving 10 or 20 miles out of their way to get a rental chassis," says Burdette. That’s because most North American ocean carriers recently stopped providing chassis as part of their service, leaving shippers and carriers to deal directly with leasing companies.

Truck drivers who haul ocean containers also contend with local highway traffic. Near the Port of Norfolk, to cite just one example, ASF’s drivers lose a great deal of time due to congestion. "It takes some drivers two or three hours to get in and out of the port," says Smith.

Once they reach the port, trucks often queue up to get through terminal gates. "The lion’s share of the trucks arrive within a two-hour window in the morning, and leave again in the afternoon," says Gary LaGrange, president and chief executive officer of the Port of New Orleans.

That causes bottlenecks. Drivers who miss their appointments to drop containers cause additional problems, especially if truckers with subsequent appointments must accommodate the late arrivals.

As such slowdowns reduce the number of round trips a drayage driver can make in one day, productivity drops. Freight stalled in congested ports takes longer to get to its destination, and demurrage charges may increase transportation costs.

Hot Competition on the Rails

Shippers who use rail intermodal face a similar issue—more freight competing for space and flowing through a network that wasn’t designed to handle that much volume.

"Intermodal has been growing consistently, but conventional rail carload traffic has jumped as well," says Larry Gross, president of Gross Transportation Consulting in Mahwah, N.J., and a partner at freight transportation forecasting firm FTR. "That’s a function of the industrial economy’s gathering strength."

Cyclical economic growth creates competition for rail capacity, but in recent years, special situations have squeezed rail capacity as well. For example, the oil boom and abundant grain harvests boosted demand for rail transportation in the upper Midwest. "That puts a lot of localized pressure on the rail network in that region," Gross says. "But because the network is interconnected, those effects tend to spread beyond the immediate area."

Railroads simply don’t have enough locomotives and crews to handle all the volume they’re seeing, Gross adds.

Harsh winters like the one the United States suffered in 2013-2014 also complicate life for domestic intermodal shippers. For instance, when temperatures plunge, the air pressure systems that railroads use to disengage brakes won’t work on long trains. "When the temperature drops down to 10 degrees, we have to shorten the train by 25 percent," says Jim Filter, vice president of intermodal commercial services at transportation company Schneider, Green Bay, Wis. "When it drops to zero, we have to shorten the train by another 25 percent."

Shorter trains mean less capacity. "Some units get left behind for the following day," Filter adds.

Freezing temperatures can also damage infrastructure. Railroads install heaters on automatic switches to keep them running in the winter, but those heaters don’t work as well in extreme cold, leaving switches vulnerable. Also, you’ll rarely see a switch heater south of the Mason-Dixon line.

"But in 2013, the winter weather traveled so far south that those areas did indeed need a switch heater," Filter says.

To better handle the flood of freight coming their way, railroads are investing millions of dollars in infrastructure improvements. In the long run, those upgrades should make life easier for intermodal shippers. But just like highway construction, work on the tracks can cause major pain in the short term.

"That construction will result in a lower average speed and more terminal dwell," says Filter. Once a railroad finishes adding new track, plus upgrades such as cranes and high-speed ramps, service will improve. "But a huge amount of track needs to get updated or expanded across the country," he adds.

Railroads have proven willing to upgrade their networks, buy new equipment, and add personnel. "It’s a question of lead time," Gross says. "You don’t just turn on the faucet and see new locomotives pour out. And crews that run 10,000-ton trains need careful training. Improvements don’t happen overnight."

A Drag on Drayage

As if overcrowded ports and tight rail capacity weren’t challenge enough, intermodal shippers also face problems finding drayage trucks—and not just because so many trucks are stuck in port traffic. The ongoing driver shortage also takes a toll.

Demand for drivers exceeds supply for several reasons. One is the Compliance, Safety, Accountability (CSA) program, a federal initiative introduced in 2010 designed to identify trucks and drivers that don’t operate safely.

"About 100,000 drivers who are no longer driving would have been behind the wheel 10 years ago," says Filter. "CSA is right for the industry; those drivers shouldn’t be on the road." But eliminating so many people from the driving pool has put a strain on trucking companies.

To complicate the situation, as the economy improves, people who used to look to trucking for employment now seek opportunities in other industries, such as construction.

"Over the past six to eight months, it has been challenging to find good, qualified drivers," says Smith, whose drayage company contracts with owner-operators. "For every 10 drivers that apply, two will pass the background checks, Department of Transportation regulations, and our own reporting."

One bright spot for drayage carriers is that most of their drivers get home every night, unlike their long-haul counterparts. "Intermodal drayage offers a better way of life for drivers," Smith says. "And with the market picking up, we’re starting to be able to push salaries up to where they’re more competitive with rates paid to long-haul drivers." To some extent, those factors could help ease the driver shortage for intermodal drayage companies.

Still, scarce trucking capacity has made some shippers desperate, Smith notes. "Customers say, ‘Tell me what I have to do to move my freight. What do I have to pay?’ We’re seeing rate increases across the board."

Inevitably, higher pay for drivers will mean increased freight rates for shippers. "Higher salaries are the only way we will be able to attract the number of drivers the industry needs," Filter says.

Chassis Confusion

While shippers struggle to find trucks to haul their intermodal freight, shippers and truckers also struggle to find chassis to put under their containers.

The problem is particularly acute for companies moving ocean containers. Starting with Maersk in 2010, most steamship lines stopped providing chassis in North America. Ocean carriers used to obtain most of their chassis from equipment leasing companies, then combine them in pools. That made wheels available to shippers wherever they needed them, without regard to the name on the equipment. A steamship line bundled the cost of a chassis into its rate for an ocean crossing.

Today, instead of dipping into ocean carriers’ pools, shippers themselves, or their truck carriers, often deal directly with leasing companies and pay a separate fee for that equipment.

The move by ocean carriers to get out of the chassis business confused the market. "Truckers said they had no idea where to find chassis," recalls Bill Knight, a founder and owner of ChassisFinder, an online chassis reservation system based in Wichita, Kansas.

Intermodal shippers often complain of a chassis shortage, but plenty of chassis are available, says Kevin Higgins, chief operating officer at ChassisFinder. They’re simply piling up in inconvenient locations. With ocean carriers no longer in charge, it can be hard to get equipment where and when a shipper needs it. "Carriers are still getting used to managing that inventory, and determining the supply and demand requirements," Higgins adds.

A small number of ocean carriers have continued to provide chassis. But even they have trouble getting equipment to their customers, now that so few carriers participate in pools.

Consider what happens when you put ocean containers on a train for transportation to the Midwest. "The lack of U.S. exports means that carriers are often stuck with chassis in locations where they don’t want them," says Burdette. "So they are stacking up in the wrong places."

The holdout ocean carriers will exit the chassis business as well by 2015 or 2016, Burdette predicts.

Smith also points to problems with lights, tires, and other mechanical features on many chassis available for lease today. "The equipment is not up to the standards it needs to be for the drivers," he says.

On the rail side, domestic chassis that vary in weight cause problems for shippers. "We might pick up a load and the scales say the weight is fine. Then we ship it across the country, it gets put onto a different chassis that is 300 or 400 pounds heavier than the one on the origin side," says Filter. The discrepancy could push the truck beyond the legal weight at the destination. "We then have to rework it, or do something different," he adds.

To compensate, Schneider advises customers to err on the conservative side when loading containers.

How Shippers Cope

Although there’s no wand you can wave to make those intermodal challenges disappear, shippers and their service providers have identified some solid workarounds. To minimize delays due to port congestion, for example, in several cities ASF Intermodal employs two distinct sets of drivers—those who haul containers between customers’ sites and the trucking yard, and those who shuttle containers between the yard and the port.

"When our road drivers reach our location, we keep them out of the port, so they don’t get delayed," says Smith. "They drop off an empty box, pick up the next load, and head right back out. That allows us to be more productive in our port locations."

At Shapiro, account representatives urge shippers to speak to port authorities about the problems they face. "We ask shippers to indicate that by shortening free time, ports put an enormous burden on the importing and exporting community," says Burdette.

The notion that shippers can convince port authorities to offer more time before demurrage charges kick in "may be pie in the sky," Burdette admits. But port operators must realize that if they’re going to deepen their channels to accommodate enormous vessels, inviting an ever-swelling flood of cargo, they need to give shippers enough time to grab their containers, he says.

For their part, port authorities and terminal operators are working to reduce congestion by upgrading facilities. "They’re adding cranes and new equipment to improve their ability to serve larger ships," says Ellis. And some local governments are building new roadways to give trucks a clear path to and from the ports, without encountering general traffic.

To reduce congestion on its property, the Port of New Orleans is upgrading the software that manages gate operations. One day, the port might eliminate gates altogether, replacing them with virtual facilities. Drivers would conduct all the necessary check-in transactions via the electronic transponders on their trucks, in an arrangement similar to an electronic tolling system.

"Moving to a virtual gate accomplishes two goals," says LaGrange. "It eliminates the space of the physical gates and creates new space to store containers."

Shapiro and many of its customers are keeping track of port labor contracts to avert delays that could arise from labor disputes, says Burdette. The aim is to try to anticipate labor conflicts as shippers and third-party logistics providers make long- range plans about which ports to use for international shipments.

Just as they develop contingency plans to deal with strikes and slowdowns at seaports, shippers need to plan around construction delays on the railroads. "They may also have to carry higher levels of inventory to deal with potential disruptions," Gross says.

Strategies for Trucks and Chassis

When it comes to securing truck capacity, shippers should give more thought to what makes their freight attractive to carriers. "As capacity continues to tighten, the economic penalty for having non-desirable freight will increase in the form of rates," says Gross.

Some shippers go out of their way to accommodate carrier needs. "Forward-thinking shippers are looking at how to expand their pickup and delivery windows, and move to more drop-and-hook freight rather than live loads," says Filter. Drop-and-hook allows a trucker to drop off an empty container and come back later to retrieve it, rather than making the driver wait while the shipper loads the box.

After the first two hours, ASF customers pay $125 per hour for time they hold drivers at their sites. "We’ve been able to convert some of our customers to drop-and-hook," says Smith. "That allows them to save money, and keeps us more productive."

For truckers and their customers who want a better way to negotiate the new chassis marketplace, ChassisFinder offers one solution. Once they register with the system, truckers use the service to search for chassis by location, date, quantity, and type, and reserve the equipment they need for pickup in any of 16 locations across the United States. "Then they bring the chassis back when they’re finished with it," Higgins says. Most customers use ChassisFinder for one-day leasing, rather than for longer-term contracts.

Currently, ChassisFinder works with just one major chassis leasing company, Flexi-Van, based in Kenilworth, N.J., but plans to add other providers in the future.

Demand for chassis through the system is lively. "We’re at approximately 90 percent usage; some locations are more than 100 percent," Knight says. To meet the need, Flexi-Van has been moving some equipment from its long-term contract pool, and bringing unused equipment back online.

Some truckers are attacking the chassis challenge by building their own fleets. ASF is piloting that strategy in Houston, where it recently put 27 of its own chassis on the road. If that works out well, the company will buy equipment for use near other ports.

ASF’s main motivation is to give its owner-operators better quality equipment. "This will help us recruit drivers, and cut down on maintenance costs and down time our drivers and customers experience," Smith says.

Schneider has bought several thousand of its domestic chassis. The company implemented some in 2013 in Stockton, Calif., then started rolling them out in the southeastern United States in 2014.

Not only has this strategy given Schneider guaranteed access to chassis, but the purchases have taken some pressure off the pools that provide domestic chassis to other carriers. Schneider also gains chassis with consistent weight, and it gets a guaranteed supply of high-quality equipment. "We will have a better maintenance program than we can from a shared chassis program," Filter says.

Shapiro, a non-asset-based service provider, is sitting down with trucking companies, chassis leasing companies, and customers to determine how to get the best possible deals on chassis leases. It’s also trying to teach importers that, now that they’re paying for chassis by the day, they can’t hold on to intermodal equipment as long as they used to.

"Long per diem now only means that the meter on your chassis is running like a madman," Burdette says. "We’re working carefully with our importers on this—how do we break their addiction to the rolling or floating warehouse?"

It’s no longer cost-effective to leave containers on-chassis in a yard until the shipper is ready to receive the cargo in the warehouse.

As it picks up speed, intermodal will continue to pose a complex set of opportunities and challenges. Shippers need to keep reviewing their transportation strategies to keep intermodal moves as efficient and cost-effective as possible.

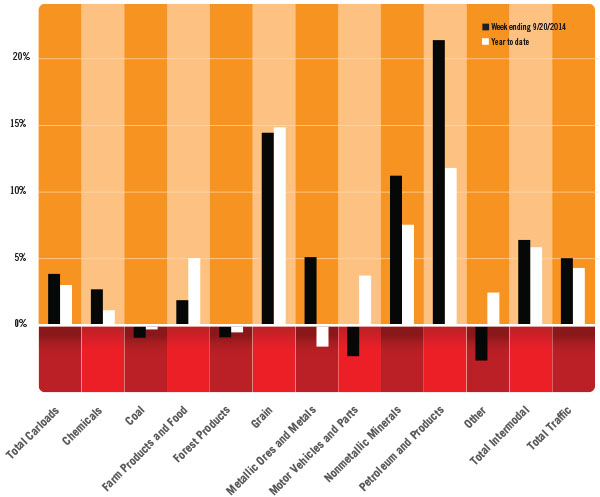

Intermodal Grows Up

Most of the commodity categories tracked by AAR saw year-over-year carload increases through Sept. 2014. Petroleum and petroleum products reported the largest growth.

North America Rail Traffic Trends, 2014 vs. 2013

Source: Association of American Railroads