Rail Intermodal: Where Rail Meets Road

Intermodal solutions gather steam as shippers track the financial and efficiency benefits of combining truck and rail transport.

The U.S. railroad has always been measured by time. At the outset, it was a uniform system to mediate time differences across the United States, and build reliability into an erratic and rapidly expanding rail network. Railroad time remains a lasting standard.

By the time the Staggers Rail Act of 1980 rolled around a century later, however, the railroad’s relevance as a mass means for moving non-commodity freight had waned considerably. It was no longer symbolic of an industrial and cultural awakening; rather, it became an indictment of an archaic and constrained mode of transport that had been quickly passed by a freewheeling motor freight industry.

Switch tracks to the present, and history is repeating itself. The transportation industry is turning back time. Supply chains have become more sophisticated in accurately forecasting and responding to demand. In turn, this flexibility allows for longer transportation moves, making time slightly less relevant. Cost and capacity are critical flashpoints, so shippers are willing to trade lead times for space availability at a lower price. They also recognize the advantages they can gain by pairing over-the-road flexibility with longer-haul economy. Past misconceptions about rail are now largely muted as industry moves toward an intermodal tipping point.

Over the past 30 years, the rail industry has made great strides re-inventing itself within a 21st-century supply chain defined by efficiency, economy, and sustainability—all hallmarks of today’s railroads.

“This is not the old railroad. In the past, rail deliveries took up to two weeks,” says Jim Kleist, vice president of operations for Railex, a Riverhead, N.Y.-based rail distribution company. “Companies that shipped by rail lived with long lead times because they had no other options. It was the nature of the system.”

“Twenty years ago, shippers perceived intermodalism as unreliable,” says John Lanigan, executive vice president and chief marketing officer for Fort Worth, Texas-based BNSF Railway. “Over time, their concerns have been erased.”

Uncorking Efficiencies

Woodinville, Wash.-based Ste. Michelle Wine Estates takes great care with its product shipments. In the wine industry, every ounce of attention and detail helps ensure the product’s quality remains uncompromised from source to cellar to sommelier. Rail transport was never a viable option for Ste. Michelle—until it began working with Railex.

Railex, which began operations in 2006, is a transportation company moving in a 3PL direction. Its U.S. network features three rail-served, refrigerated mega-transload distribution centers in Delano, Calif.; Wallula, Wash.; and Rotterdam, N.Y., and a 55-car refrigerated unit train with multiple weekly departures. Railex’s service can transport the equivalent of 220 trucks of refrigerated merchandise coast-to-coast in five days.

The rail carrier’s on-time assurance turned Ste. Michelle in its direction. “Railex is located just 40 miles from the Columbia Crest winery, our major production facility,” says Rob McKinney, vice president of operations at Ste. Michelle Wine Estates. “The price of fuel was rising, so we consulted Railex.”

The winery had explored rail transportation before, but never found the appropriate circumstances or partner to meet its stringent requirements.

“We evaluated rail shipping, and considered the metrics of breakage, product damage, and temperature control, but couldn’t find a way to bridge our quality concerns to minimize damage and move shipments efficiently,” says McKinney.

Careful attention to temperature control and handling during warehousing and intermodal transport helps ensure the quality of Ste. Michelle Wine Estate’s products.

Careful attention to temperature control and handling during warehousing and intermodal transport helps ensure the quality of Ste. Michelle Wine Estate’s products.

In previous test runs, the rigors of intermodal transit resulted in bottle scuffing and product damage. Temperature is the biggest concern. If it’s too cold, certain wines produce sediment or tartrate fallout; conversely, too much heat can push the cork and oxidize the wine. Ste. Michelle’s second-highest expense after the wine is its packaging. Damage to either is unacceptable.

But the winery’s business was growing, and it needed a partner to manage its transportation and logistics. “We had been our own distribution point and warehouse, and oversaw truck traffic and orders,” McKinney says. “We reached the point where it would require significant capital to expand infrastructure.”

Railex was well aware of Ste. Michelle’s expectations when the carrier entered the picture. “When you ship French fries, for example, you deal with experts in moving frozen food,” says McKinney. “But when you manage wine, you may be dealing with the winemakers. It’s their passion, their creation—an art form.”

Railex proved to be up to the task, providing reliable and secure five-day service from Wallula to Rotterdam. The railcars are temperature-controlled, and Ste. Michelle can track the shipments during transit. With pre-determined temperature thresholds in place, it can be alerted if conditions change. Then Railex can coordinate with its rail partners—Union Pacific in the western United States and CSX in the eastern states—to manage the problem.

The transportation company’s value to shippers is its capacity to be multi-dimensional. In addition to moving product by rail, it also stores inventory and arranges truck transportation—which is especially convenient for Ste. Michelle on the East Coast, where it imports product from partners in Italy. Railex can move shipments via truck out of its Rotterdam facility instead of sending them to the West Coast for re-distribution.

Prior to working with Railex, Ste. Michelle was transporting approximately two million cases per year by truck, in 10 to 15 loads daily. While it still uses over-the-road transport to make shorter-haul deliveries in the west, the rail/intermodal component now serves a large share of its business.

Railex moves roughly one million cases annually, and stores about 500,000 units. More telling, it can squeeze three times as much wine on a train than a truck, which provides considerable sustainability gains in terms of reducing fuel use and carbon emissions.

Pulling the Trigger

Ste. Michelle’s patience in waiting for the right opportunity to come along before it made the switch to intermodal has served the company well. For other intrepid users that jumped in early on, experiences weren’t always successful.

“Some shippers started using intermodal extensively, and the results weren’t always what they expected,” says Dave Howland, vice president of land transport services for APL Logistics, a global third-party logistics (3PL) provider with U.S. headquarters in Scottsdale, Ariz. “Companies coming back into the marketplace now are more disciplined—opening one lane, then another. They are working their way into the business rather than jumping in with both feet. That works better, because they are in a more controlled environment.”

The 3PL only recently re-entered the domestic market after a 10-year absence following ocean carrier NOL’s acquisition of its steamship line and divestiture of the intermodal business. APL Logistics continued to invest in and develop intermodal capabilities elsewhere around the world, and by 2011, the time was right to get back into the U.S. domestic game. “Many ocean shippers were asking when we’d begin serving them domestically again,” Howland explains.

APL handles half a million intermodal loads annually, including 100,000 automotive moves between the United States and Mexico, so getting back into the U.S. game didn’t require a huge leap of faith. Plus, U.S. market demand for intermodal has been on a marked growth trajectory.

In the first quarter of 2012, domestic intermodal container volume increased 14.9 percent year-over-year, according to the Intermodal Association of North America’s Intermodal Market Trends and Statistics report. Gains were largest in the east, where intermodal faces more competition from trucking.

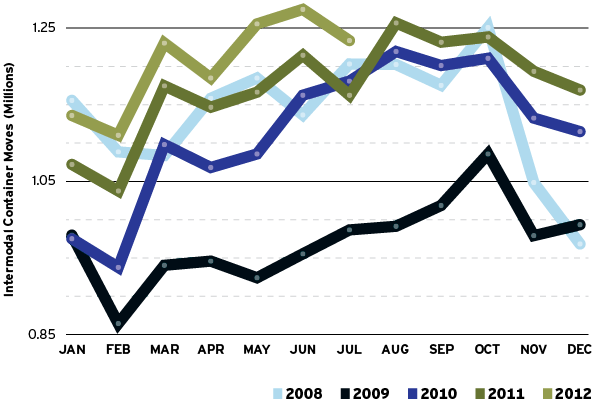

In 2011, intermodal container volume set a new record with 12.4 million moves, surpassing 2007’s record year by nearly four percent. Over the past five years, international and domestic growth has progressed at a steady clip, despite the recession (see chart, below).

The reasons for this surge are myriad. Welch’s, a Concord, Mass.-based food manufacturer famous for its grape juice, made the switch to intermodal about four years ago—largely to offset rising fuel costs, but also to achieve sustainability gains.

Intermodal Traffic: Movin’ On Up

Over the past five years, international and domestic intermodal traffic has grown steadily overall, despite the recession. In 2011, more than 12.4 million intermodal containers moved worldwide.

Source: IANA Intermodal Market Trends and Statistics

“Intermodal was a less expensive approach,” says Dan Biggs, director of customer logistics, Welch’s. “The downside lies in the longer lead times, which are not always well-received by customers.” Consignees often fear rail service is inconsistent, or that they will have to hedge risk by carrying more inventory.

Intermodal is a small part of the total freight mix for Welch’s. The company has used it in certain lanes—such as between Michigan and the Pacific Northwest, and from Erie, Pa., to Florida—where it doesn’t have a distribution presence or can get competitive transit times. It also has the ability to switch between intermodal and truck transport, as it plans to do in the Pacific Northwest per promises to customers.

While some shippers foreign to intermodal are still cautious, there are also reasons for optimism. For example, on-time delivery times are becoming more competitive with trucks in certain lanes.

“Intermodal services are becoming more dependable, with most service lanes in the high-90 percentile for on-time delivery,” says Howland. “Industries across the board are coming to us. If fuel costs stay high and the driver pool remains tight, intermodal will be more competitive in the 700-mile length of haul. In the eastern United States, it is used for even shorter distances.”

Improved service levels, the environmental benefits of converting truck to rail, and the availability of capacity are all intermodal drivers. “The flex capacity that rail brings—such as the ability to add units or train starts—allows responsiveness not available to motor carriers that are overbooked or short of drivers,” says Lanigan. “The threat of a driver shortage has caused shippers to hedge bets in case the trucking industry experiences capacity issues. The move to intermodalism is a combination of all these factors. Are they weighted equally? No. Each shipper has its own trigger points.”

After the Conversion

Ste. Michelle’s trigger was recognizing it could transport product across the United States more economically and sustainably without sacrificing quality. That its partnership with Railex has moved beyond a functional need and now allows it to grow more organically on its own is an added bonus.

“Handing off transportation to an expert allowed us to focus on our core business,” says McKinney. “We’re maintaining our staff; we haven’t reduced labor. We’re taking the opportunity internally to re-train employees and build a flexible, agile, cross-functional work team that can float anywhere within our winery operations.”

As Railex expands its network—it is considering a distribution location in the Southeast—Ste. Michelle benefits by being able to deliver product closer to customers via rail, reducing the last-mile dray. Intermodal also provides a security blanket as looming capacity concerns threaten transportation economy and efficiency.

“Shippers are weighing two factors: transportation costs and space availability,” says Kleist. “Where is capacity, and what will it look like down the road?”

Ste. Michelle’s conversion has also compelled it to evaluate all the inbound raw materials it transports via truck—empty glass and packaging, for example—to determine if there is an opportunity to use rail.

“We transport thousands of barrels by truck annually,” says McKinney. “We can analyze our freight needs to determine if it makes sense to leverage rail and Railex’s buying power with other carriers. We’ll consider anything that increases efficiency and improves quality.”

Ste. Michelle expects Railex to eventually take care of special projects, such as export orders that require compliance labeling. The service provider may also manage Ste. Michelle’s direct-to-consumer business, because it is already tasked with storing inventory and building orders. All these functions are currently performed on- site at the winery’s Columbia Crest facility. In the future, they will be transitioned to Railex to free up space and resources.

“If we’re holding all the product, we need to be able to perform the peripheral tasks,” says Kleist. “Our focus is on ensuring we provide the necessary care, custody, and control through the rest of the chain, from pickup to delivery. Ste. Michelle and Railex are finding all the savings possible in the entire process.”

No Time Like the Present

As a transportation concept, intermodalism is far from new. It has always been an important part of the global supply chain. Motor freight is the anchor at both ends of the divide, with air and ocean in between. But on the U.S. domestic side, intermodal has never been compulsory. Ample opportunities exist for shippers and consignees to leverage the economy of rail transport—whether it’s converting truckloads to railcars, or expediting containers in and out of congested cities and ports.

Intermediaries such as Railex and APL Logistics understand the value of pushing more freight onto the tracks, as well as their importance in liaising between railroads, shippers, and truckers.

“We view our role as being an integrator,” says Howland. “Many shippers have outsourced transportation management, not just intermodal, to us. Our goal is to take the entire book of freight, find the best solution, and uncover more intermodal and load consolidation options. We’re converting 10 to 15 percent of over-the-road moves to intermodal with many customers.”

The railroads play their own unique role, as well. For example, BNSF Railway’s Next Generation Intermodal service provides a platform for trucking companies and shippers to work together more collaboratively.

“We’re rewriting the script on what an acceptable dray is from a length-of-haul standpoint, and how shippers can access denser markets and take advantage of intermodal opportunities by draying a little farther to origins and destinations,” says Lanigan.

Then there’s the matter of site selection. Railex’s Wallula distribution center is 40 miles from Ste. Michelle’s Columbia Crest winery, providing a relatively short truck haul by West Coast standards.

“In eastern Washington, many frozen and fresh food processors are migrating from the west side of the state closer to where the product is being grown,” explains Kleist. “Companies may follow a similar pattern with transportation. Businesses gain options if they are located near an intermodal facility. Intermodal won’t be the complete answer for every company, but it can be a bigger part of the solution.”

Some companies are looking to locate even closer to intermodal ramps so they can radically reduce trucking costs. Lanigan cites retailers that move a high volume of low-value product and can pad the bottom line by using rail. Craft supply retailer Michaels Stores, for example, has a major distribution center near BNSF Railway’s intermodal facility in Fort Worth. Companies that locate DCs in these areas can greatly reduce drayage time and expense.

This type of exposure is having a sea-change effect within the transportation and logistics sector. As more well-known brands make the jump, they raise the profile of intermodal solutions, making them an easier sell for carriers such as BNSF Railway. “When you can show a prospective customer a list of top companies that are moving freight with you, it’s pretty tough for them to say intermodal can’t work,” notes Lanigan.

The change in industry’s perception of intermodalism is pervasive enough that the only pockets of resistance Lanigan sees among shippers tend to be generational—people who were around 15 to 25 years ago and had a negative experience in intermodal’s early days.

Industry has come a long way in mediating the complexity of moving freight between modes and ensuring visibility through interchanges. The execution piece is no longer the sticking point. “What challenges us now is skepticism,” says Kleist.

For companies such as Ste. Michelle, Welch’s, and Michaels Stores, few doubts linger about intermodal’s potential. Its time is now.