Inspecting the Unexpected: The Science of Packaging Perfection

Avoid these 10 common packaging mistakes to keep high transportation costs and inefficiencies from boxing you in.

Packaging Design and the Environment

3PL Partner Identifies Packaging Opportunity for Entrust Datacard

Is the Best Box No Box?

When is a box not just a box? When it represents your brand, advances your green initiatives, prevents costly damage, and helps limit the impact of dimensional (DIM) weight pricing for parcels measuring less than three cubic feet.

The advent of small parcel DIM weight pricing, which took effect on Jan. 1, 2015, for shippers using FedEx and UPS, is just the latest factor driving interest in optimizing packaging. While packaging has sometimes been the neglected stepchild of supply chain decision-making, its potential to contribute to greater efficiency and an improved customer experience is helping to raise its profile.

“Many companies see packaging as small potatoes,” says Jack Ampuja, president of Getzville, N.Y.-based management advisory firm Supply Chain Optimizers. “But the key is not the cost of the box, it’s the impact on efficiency. It’s possible to save $1 million depending on the choice of box, but many companies don’t do their homework.”

That means many shippers are missing out on packaging savings. They are not only paying more than they need to for parcel shipments, they are also overlooking multiple opportunities to ship more efficiently up and down the supply chain, and support myriad other business goals—from embracing sustainability to enhancing customer satisfaction.

Here are 10 common packaging errors, and advice on how to correct them.

1. Underestimating the impact.

Parcel shippers who failed to act after DIM weight pricing was announced are already paying the price through increased shipping rates. According to industry estimates, shippers pay about 30 percent more if shipping the same items under DIM versus weight-based pricing, and that’s apart from the nearly five-percent rate increase that went into effect for many shippers in 2015. Savvy shippers acted proactively. Some negotiated in advance to postpone their rate increases, while others undertook packaging optimization projects to make parcel shipping more efficient. But it’s never too late to start, and minimizing DIM weight is not the only way to achieve savings.

For example, Supply Chain Optimizers helped one nutraceuticals manufacturer increase the strength of its cartons so they could be stacked onto pallets for the first time, significantly increasing space utilization. The consultant also managed an optimization project for slipper company R.G. Barry that included replacing weak, shallow boxes imported from China with deeper, stronger corrugate and changing how the slippers were packed. This project reduced R.G. Barry’s corrugate spend by 15 percent, cut inbound freight costs by 20 percent through eliminating 600 ocean containers, and reduced storage costs by 25 percent. Those reductions saved $2.5 million annually.

Packaging efficiency improvements can have a cascading impact—from the individual product or case level all the way up to containers. “If we can bump up an ocean container from 60 percent to 80 percent density, by the end of the week we’ve used two fewer containers,” says Michael Labadie, director of global solutions at Crane Worldwide Logistics, a third-party logistics (3PL) provider based in Houston. “Good things happen if we can ship full containers—not only transportation savings, but also lower forwarding fees, fewer broker entries, and fewer containers causing congestion in the port.”

Another important, although softer, benefit is the positive impression good packaging can deliver. A consumer survey conducted by Charlotte, N.C.-based packaging maker Sealed Air finds that 66 percent of Americans agree that how their shipment is packaged reflects how much a retailer cares about their order, and 48 percent think packaging quality reflects the value of the product (see Packaging Design and the Environment sidebar). About half of responding consumers get a negative impression when orders are over-packed, the survey notes.

2. Leaving packaging up to partners.

Few contract manufacturers in Asia have significant expertise in packaging. Given the distance those cartons may travel—via container, and then truck or rail—small improvements in density can have a large impact on efficiency. It pays to ensure good protection and density by making your own packaging decisions rather than leaving it up to your suppliers.

3. Dismissing the complexity.

Improving the packaging of your products can be complex. And nowhere is packaging more complex than in e-commerce, where the number of SKUs multiplied by the possible combinations of items in a customer’s order makes for millions of different potential weight and cube requirements—all of which the average packer, often incented on productivity, has to match on the fly to a limited range of box choices. In most e-commerce shipments, the product takes up no more than 60 percent of the box volume, according to Supply Chain Optimizers.

Even a predictable packaging task, such as boxing up identical items coming off the production line, can be tough to optimize, with hundreds of possible configurations of product inside a carton, multiplied by a variety of box options. And customized cartons present even more possibilities.

Packaging optimization strives to overcome those complexities by finding the right balance between two conflicting forces: product protection and cost. “Too little packaging can cause item damage, product waste, return shipping costs, and lost customer trust,” says Ron Sledzieski, executive business director, global-Instapak, for Sealed Air. “Too much or the wrong packaging can result in environmental implications and higher costs for the shipper.”

4. Neglecting sustainability

Increasing density has ripple effects across the supply chain, making every move more efficient and, in turn, reducing carbon footprint. But that’s not the only impact packaging can have on sustainability. Consumers demonstrate an interest in buying from companies that make them feel good about their purchases. The packing materials market has responded by developing greener alternatives to environmentally unfriendly materials such as polystyrene, and seeking ways to ensure the recyclability of the packaging materials they use. Steady improvements mean many green products made from agricultural waste, pulp, and mushrooms, now offer comparable performance and pricing to petroleum-based materials.

“Sustainability is huge as it relates to shipping and package design,” says Kevin Fletcher, senior vice president at Kenco, a 3PL based in Chattanooga, Tenn. “Many companies that consider new package designs are responding to customer desires, but other factors to consider include government and environmental agency regulations regarding materials, products, and compositions. They see green initiatives as a source of innovation for their companies.”

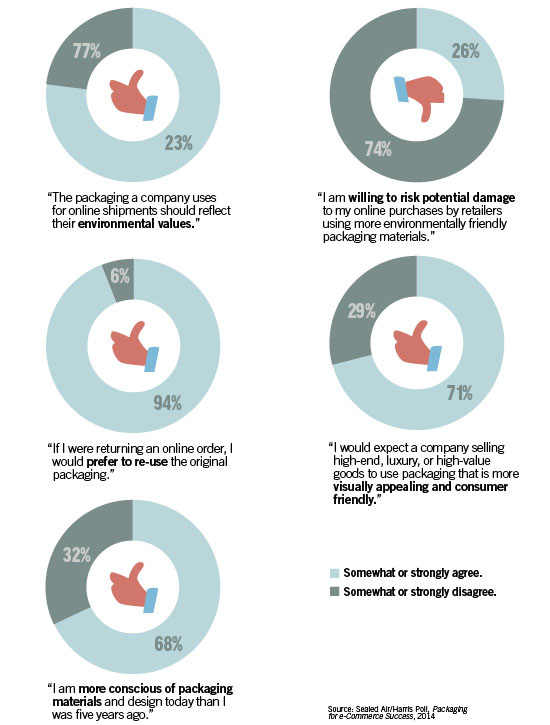

Sealed Air’s survey finds 68 percent of American consumers are more conscious of packaging and design than they were five years ago, and 77 percent agree an online company’s packaging should reflect its environmental values.

For example, recycled denim fiber takes the place of polystyrene in MP Global Products’ solution while offering comparable R-values and cost, says Roger Borgman, national sales manager for the company’s Thermal Packaging Division, based in Norfolk, Neb. The denim biodegrades in less than one year, while the poly liner takes a little longer to break down. Because the two-part system—walls and lid—is custom cut and compressable, it absorbs shock better and eliminates molds. Shippers can fit 20 to 50 percent more denim fiber on a pallet versus polystyrene, although it offers less support, Borgman says.

Similarly, Sealed Air has introduced a variety of sustainable packaging materials, including a high-efficiency packaging foam that offers better performance in less space.

5. Reducing box selection.

Reducing SKU count is a time-honored way to trim costs. But in the case of boxes, savings are often found by adding rather than reducing options. A larger array of packaging increases the odds of maximizing the density for a particular order.

It’s not really about the box.

“Out of every $1 in an e-commerce supply chain, less than 10 cents is in the box,” says Supply Chain Optimizers’ Ampuja. “The other 90 cents is in labor and freight costs.”

In fall 2014, SCI Logistics, a 3PL based in Canada, implemented a new packaging strategy that increased its box choices from seven to 12, while also changing the strength of the boxes to better match needs. To date, it has netted better cubing and fewer damages to customer shipments.

Moving forward, “we expect to decrease corrugate spend, reduce transportation costs, and increase customer satisfaction,” says Tim Pyne, general manager, retail services for SCI Logistics. In addition to changing the array of boxes, it sometimes helps to ship a single order in multiple boxes, Pyne adds, although this tends to be less popular with customers.

Some shippers worry that selecting a box closer to the size of the contents compromises the ability to ward off damages. But any loss of protection in box size can often be made up with better packaging. “In the end, you’ve reached the same goal of reducing shipping costs,” notes Sledzieski.

6. Ignoring alternatives

Sometimes the best box is a pouch, or a tote (see Is the Best Box No Box? sidebar), or even a different grade of corrogate. A big part of reducing DIM weight is cutting air out of the package, something an envelope or poly bag does well for small items.

Packing material represents another area for considering alternatives. Packing material manufacturers are continually refining their product lines of sustainably sourced materials (see Mistake 4). But sometimes, finding alternatives is simply a matter of being open to new packing techniques, such as using plastic film to suspend a product in the center of the box instead of using loose fill.

7. Getting the wrong kind of help.

Much like industrial, aircraft, nautical, or any other type of engineering, package engineering requires a specific set of skills. An optimized package balances competing priorities—protection and cost efficiency. But many companies assign the task to internal engineers who lack the correct expertise.

Companies can find packaging help from a variety of sources—from packaging materials manufacturers to design firms to independent consultants. Recently, many 3PLs have tossed their hats into the ring as well, viewing packaging efficiency from a supply chain perspective.

“Packaging is our secret sauce,” says Crane’s Labadie. “As a 3PL, we find that companies make packaging decisions for various reasons—manufacturer convenience, lifecycle, presentation to customer—but not for optimizing the supply chain. We look at the supply chain impact versus the actual packaging itself.”

Crane sometimes works in concert with a packaging partner, but always applies its logistics perspective to the task. “Packaging manufacturers make packages for the sake of making packages,” Labadie notes. “They may not consider how the box will be used, or how it moves through the supply chain. We have a broader scope, because we work in every industry vertical.”

Similarly, SCI Logistics and Kenco offer their clients consulting services around their packaging, sometimes in conjunction with third-party packaging experts. For customers impacted by the shift to DIM weight pricing for parcels, for example, “We work with them on parcel analysis, to see how much of their business is affected, their packaging characteristics, and the financial impact,” says Kenco’s Fletcher. “In some cases, packaging improvements require minimal effort, while in other cases, there is more upstream involvement.”

8. Selecting boxes and building cubes manually.

In e-commerce packing operations that rely on manual box selection, packers grab the wrong box about 25 percent of the time, according to Supply Chain Optimizers. Incenting packers around efficiency, not just productivity, can help.

Another solution is implementing box optimization software. Atlanta-based advanced planning and optimization service and solutions provider ORTEC says its technology improves box utilization by 15 percent, cuts costs by 40 percent, improves pick/pack labor efficiencies by 20 to 30 percent, and reduces carbon footprints by using less corrugate.

Software is the next step in SCI Logistics’ packaging initiative. “Packers currently make the decision on the box,” says Pyne. “As we improve weights, and especially master data information, we plan to implement software to better identify the right size box.”

Load planning software can also act as a complementary technology, which helps ensure pallets are built to maximize use of space, and trucks are optimally loaded.

9. Working in a silo.

Packaging affects a surprising portion of an organization, and decisions made in one group can impact the ability of another to reach its goals. A small change to product packaging, for example, impacts the size and type of carton used to pack it, as well as packing materials used. That, in turn, can impact how the product is palletized and how it moves through the supply chain.

The appearance of packaging is also a concern: The box may need to attract attention and tout product features, and the presentation affects customer impressions. But features that make the box pretty may not stand up to current handling practices. So any well-considered packaging initiative needs to include representatives from sales and marketing, transportation, warehousing, sourcing/procurement, production, and finance.

Cross-functionality is not the only consideration. Companies must factor in many trade-offs. Packaging changes made to accommodate one group may inadvertently impact another, adding steps or costs to their processes. “Four budget holders might have completely different ways to measure their business,” says Crane’s Labadie.

10. Not preparing for returns.

Up to one-third of e-commerce purchases are returned, according to retail consulting firm Kurt Salmon. But with the category’s fast growth, few companies have looked closely at packaging in the returns process. That can be a costly oversight, particularly for those offering free returns in the DIM weight pricing era.

“When you leave return packaging to the consumer, inefficiency goes through the roof,” notes Ampuja.

Some retailers are beginning to design outbound packaging with returns in mind, not just by enclosing returns paperwork, but also by designing packing materials and boxes that are reusable, intuitive, and strong enough to make a return trip. Designing returns packaging prevents damage, and is more convenient for the consumer.

For shippers with high return rates, “It’s in their best interest to use the most efficient package to ship and to minimize damage on eventual returns,” says Fletcher. Those efficiencies may include reusable containers, and/or a pouch or a box that can be resealed.

Looking Ahead

DIM weight may be the current focus in parcel shipping, but “Less-than-truckload (LTL) is not far behind,” notes Ampuja. LTL shippers often don’t know, or they understate, their freight class. Instead of taking risks by basing pricing on weights at potentially wrong rates, some LTL carriers are installing dimensioning systems that use lasers and scales to calculate a package’s weight, cube, and density, along with recording the date and a photo of the shipment. They can then charge based on accurate weight and freight class.

“For one LTL carrier, this system paid for itself in three weeks,” Ampuja says. A few carriers have already implemented density-based pricing for LTL, while others are currently making it voluntary. “We expect the tipping point in fewer than two years,” he says.

With all the changes and opportunities, it’s time for packaging to gain a higher profile in supply chain discussions.

“Packaging is a brand differentiator, and offers an opportunity to highlight your company as environmentally friendly,” says Kenco’s Fletcher. “As long as advancements in technology continue, packaging is an area companies should revisit at least annually.”

Packaging Design and the Environment

A recent Sealed Air/Harris Poll survey examined the role packaging plays in e-commerce, and how the presentation of products impacts the customer experience and consumers’ image of retailers. A majority of respondents said they are more conscious of packaging materials and design today than they were five years ago. Here are other key findings.

3PL Partner Identifies Packaging Opportunity for Entrust Datacard

Governments, financial institutions, retailers, and other organizations worldwide use Minnetonka, Minn.-based Entrust Datacard’s card printers to issue more than 10 million identity and payment credentials every day.

The company manufactures many of its enterprise made-to-order and desktop printers in Minneapolis, and used to send weekly shipments via ocean container to overseas customers, which was a costly proposition.

To minimize those costs, the company decided on a two-stage approach to serve its Asia-Pacific customers. First, it established a distribution facility in Hong Kong through its third-party logistics (3PL) partner, Crane Worldwide Logistics. Then, it looked to revise how its printers, parts, supplies, and consumables were packaged. “Working with a 3PL allowed us to look at container utilization, and reduce freight costs to the region,” says Marc Schopp, director of global logistics for Entrust Datacard.

Protecting sensitive printers from damage that can occur during ocean transport requires overpacking. But this level of protection is not needed once an order shifts to ground transport; it just runs up costs. Entrust Datacard also wanted an attractive package for its customers to open, but “pretty boxes don’t look as pretty after a one-month ocean journey,” Schopp notes.

Today, Entrust Datacard can focus on making ocean movements as cost efficient as possible for Asia-Pacific customers. When a container reaches its new Hong Kong DC, Crane staff repackages selected orders for attractive and efficient parcel delivery.

In addition to enabling more cost-efficient movements, the two-part strategy reduced negative feedback on shipping issues from Asia-Pacific customers by 25 percent. These results drove Entrust Datacard to award Crane a similar 3PL contract in Brazil.

Is the Best Box No Box?

The trend toward smaller formats in retail has a collateral effect: How to make efficient deliveries through narrow rear doors into tiny back rooms. Suppliers such as Orbis, an Oconomowoc, Wis.-based provider of bulk containers, pallets, and protective dunnage, think they have the answer: Get rid of the box entirely.

Currently, store orders are often picked to cartons, built into pallets, and loaded into trailers. Then the driver manually retrieves the order, and places cartons onto a hand cart or conveyor to fit through the back door. The store needs labor to receive the order, stage the boxes, replenish the store floor, and compress the corrugate.

Orbis provides alternative solutions that combine plastic totes, dollies, and pallets to minimize touches, avoid the need for hand trucks or conveyors, eliminate carton disposal, and enable goods to move right from the truck to the store floor. Warehouses build the store’s order right onto the reusable totes, which move easily from truck to store floor, with totes picked up on the next delivery.

The return on investment comes from efficiencies in truck usage, labor, materials handling equipment, and increased throughput, with sustainability benefits as well.

“We used time and motion studies to make the process more efficient,” says Mike Ludka, product manager, retail supply chain, for Orbis. “We’re breaking down the silos between the steps of the supply chain, delivering savings all along the way.”