Perishable Logistics: Cold Chain on a Plane

Careful planning for perishable air cargo helps shippers keep their cool.

In perishable logistics, time is of the essence to ensure produce, flowers, fish, and other products reach their destinations while they still offer maximum appeal and shelf life. As a result, many of these goods move via air.

But the potential complications of shipping perishables via air are legion: The trans-Atlantic airfreight space for a produce shipment is booked—but the peppers aren’t ready for harvest. Top New York chefs are writing premium Icelandic cod into their menus in anticipation of delivery—but the fish is sitting in a fog-induced backlog at the Keflavik airport. Holland tulips are loaded into the belly of a passenger aircraft—but then the pilot orders several coolers pulled off to free up weight for extra fuel.

The uncertainty inherent in grown or caught product—combined with the potential vagaries of air transport—means managing perishable logistics demands specific expertise. "The greatest challenge is to maintain the cold chain, which varies from product to product," says Alvaro Carril, senior vice president of sales and marketing for LAN Cargo, a cargo airline based in Santiago, Chile, and a subsidiary of LAN Airlines. LAN Cargo transports salmon and fruit from Chile, asparagus from Peru, and flowers from Ecuador and Colombia to the U.S. market.

"Transporting salmon is different than moving flowers, and both commodities require special and differential treatment," Carril notes.

Perishable logistics is an evolving science, as changing consumption patterns, variable regulation, rising customer expectations, and shifts in services converge to create a complex and changing supply chain.

Pineapples on Board

Perishables shippers use both passenger aircraft and freighters to speed goods to their destinations, according to market needs, the nature of the commodity, product margin, and individual preferences.

Passenger flights are generally more frequent, less expensive, and more widely available, but they require adherence to tight timetables, and goods may get bumped at the pilot’s discretion. Freighters offer better temperature control, fewer inspections, and additional capacity, which is particularly valuable for large quantities of short-season goods. But freighters can be more costly, may fly less often and to fewer locations (depending on the region), and may sit until they reach capacity, endangering perishables.

Air cargo has long competed with ocean shipping for some perishables commodities. One common pattern is for the beginning-of-the-season harvest to ship via air so it’s first to market, followed by ocean shipping as the full season gets underway, says Markus Fellmann, global vice president of Hellmann Perishable Logistics, a Miami-based unit of third-party logistics (3PL) provider Hellmann Worldwide.

Pineapples and stone fruit, with their long shelf lives, have been shippable via ocean for some time. Today, scientific advances —such as specialized packaging that extends produce lifecycles—are enabling additional commodities to move via steamship. For example, Chiquita Brands International subsidiary TransFresh Corporation creates controlled-atmosphere containers and techniques that are driving interest in ocean transport for other types of fruit.

Other perishable goods are also more commonly shipped via ocean. Between 30 and 40 percent of the volume of cut flowers from Colombia, and 20 percent of those from Kenya, could move via steamship within five years, according to some estimates.

But, steamship lines’ efforts to reduce fuel consumption by traveling more slowly has forced some perishables commodities back to air cargo. Trips from Holland to New York that once took seven to eight days can now take 12 days on the water.

"In the past, we moved a lot of bell peppers in sea containers to the United States, but in the past five years, the volume has decreased," says Marcel van der Pluijm, account manager, United States and Canada, at Global Green Team, a fruit and vegetable trading company in Maasdijk, Holland. "Transit times are too long by steamship, so 99 percent of peppers move by air."

The air or sea choice comes down to what value a producer is seeking to deliver—and it is often a matter of taste versus price. "A mango shipped by air has a different taste and quality than one shipped by sea," says Uta Frank, product manager, perishables, for Lufthansa Cargo, the Frankfurt, Germany-based air cargo subsidiary of Deutsche Lufthansa AG.

A Fleeting Concern

Thanks to increased air cargo volumes for commodities such as flowers, perishables supply chain executives report a slow but steady rise in air cargo use. But one development with the potential to significantly impact perishables movement is the transition of airline passenger fleets to new, more environmentally friendly models. Fewer available widebody aircraft threatens to reduce cargo capacity and dimensions, impacting perishables shippers reliant on those routes.

Another factor is the ongoing transformation in both product growth and consumption. In Europe, for example, "domestic production in North America and Latin America is a big challenge and threat to overseas exports from Europe," says van der Pluijm. That has European producers eyeing emerging markets such as China and India.

The increasing globalization of perishables comes with some trade-offs. Food safety incidents that once would have been locally contained now have the potential to spread across the globe. Over the past few years, for example, a "Fish Farmageddon" has been underway among salmon farms due to Infectious Salmon Anemia (ISA) virus, which poses no proven health risks to humans, but kills fish.

The virus is threatening native salmon in countries that import it, leading to bans. Chile reportedly lost $2 billion and more than 25,000 jobs during an ISA crisis in 2008. Although the country has mostly recovered, the virus re-emerged there in 2012.

To try to control foodborne illness, the United States passed the Food Safety Modernization Act of 2010, which gave the Food and Drug Administration more power over safety and recalls. Traceability requirements are expected to follow. In the meantime, the produce industry formed the Produce Traceability Initiative, a voluntary, industry-wide effort to maximize the effectiveness of existing track-and-trace procedures. "We all eat, and we want our food to be safe," says Christopher Connell, president of Commodity Forwarders, a Los Angeles-based freight forwarder specializing in perishables.

Other governments have also begun to issue regulations, but different countries and jurisdictions adhere to different standards, complicating compliance.

One step to safety is guaranteeing the cleanliness of food-grade containers. It is critical that companies packing the containers have processes in place to ensure adherence to cleanliness standards. "The industry is proactive when it comes to cleanliness, because it helps reduce claims," says Fellmann. "And no one likes to deal with claims."

Pests and parasites are an important concern, with some countries requiring fumigation of certain import products. Produce, for example, is inspected by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), which sends any unknown insects it discovers to a lab for analysis. Different countries have different policies about what bugs are acceptable.

The safety of perishable goods themselves is not all that is at stake. Homeland Security regulations that began requiring 100-percent inspection of all passenger aircraft cargo in 2010 include perishables. But inspecting cargo takes time—and time is not on the side of perishable goods. So instead of waiting for government inspection, a number of freight forwarders have attained the credentials required to inspect and certify that perishables shipments are free of devices of terrorism. This requires them to invest in worker training and certification, develop secure processes, and implement physical security systems.

Peninsula of Boston, for example, is an independent transfer point for fresh food distribution in the Northeast, and a Certified Cargo Screening Facility that inspects fresh fish traveling on passenger aircraft.

"The cargo volume is too great for the airlines to handle," explains Joseph O’Neill Jr., vice president of business development at Peninsula. The company also acts as an indirect air carrier, receiving, booking, packing, sealing, and handling documentation for seafood wholesalers.

Streamlining Clearances

Perishables handlers take great pains to ensure customs clearances go as smoothly as possible, so goods don’t sit idle. Experience and long-term relationships with customs go a long way toward making that happen.

One location that has expediency down to a science is Miami, where about 90 percent of imported flowers enter the United States. The majority of those flowers come from Colombia and Ecuador. An average of seven daily flights, six days per week, carry nothing but flowers into the United States, says Christine Boldt, executive vice president of the Association of Floral Importers of Florida, a Miami-based trade group. Steamships have traditionally been used only for major events such as Valentine’s Day or Mother’s Day.

One for All

Due to this massive volume, U.S. Customs and Border Protection has given the port’s air carriers authority to act on importers’ behalf, managing the entire planeload as one shipment instead of handing off clearance responsibilities to the 30 or 40 brokers that may be involved in a single aircraft’s payload.

"The air carriers prepare the paperwork and sampling, and show the product to customs," says Boldt. "A farm may ship to several customers, so instead of inspecting multiple times, customs can do it once." Customs operates around the clock, and the USDA also offers extended hours to speed processing.

Incoming freighters travel directly to coolers at Miami International Airport within minutes of landing. LAN Cargo, for example, operates a 430,000-square-foot cold storage facility on site, with 161,460 square feet acclimatized and outfitted with specialized equipment to handle perishables. The company has invested $8.3 million in cold infrastructure since 2010.

Neighboring the Miami airport facility are two fumigation plants, and importers are all located within five miles of the airport so they can quickly come pick up goods. At least 25 ground carriers specializing in flowers are based in the area, all set up to speed deliveries to their destinations across the United States. Most flowers travel via the boxes they were packed in, but supermarkets and mass merchants require that shippers open the boxes, cut and package the flowers, then place them in standup bucket boxes.

The entire trip from South American farm to North American retailer can take as few as four days. The speed is essential to provide a positive flower purchase experience and drive repeat purchases.

When a harvest or fishing season begins, companies in the perishables supply chain are eager to be first to market. That means stiff competition for limited capacity in the bellies of passenger aircraft, or coordinating shipments from enough farms or producers to fill a freighter.

"To accommodate peaks, we handle full charter, and we negotiate block space agreements with certain carriers for daily, weekly, or monthly allocations," explains Fellmann. Backhaul capacity may be used to deliver consumer goods or electronics to destinations that supplied flowers, fish, or produce.

Perishables customers want logistics partners that can ensure access to capacity, cool facilities in as many steps of transport as feasible and affordable, and the ability to move goods rapidly and on time.

Another growing demand is for end-to-end service. With sourcing from more diverse locations, perishable supply chains have become crowded; shippers are seeking service providers who can manage multiple suppliers and/or provide a range of services under a single banner.

Kuehne + Nagel, a global third-party logistics provider, for example, recently opened an accredited airfreight station at New York’s John F. Kennedy Airport to ensure seamless cold chain integrity for temperature-sensitive air cargo. That step enables the company to manage all logistics and brokerage tasks so the shipper receives one invoice, rather than several.

Experience is critical to understanding the characteristics and needs of each commodity, so many forwarders, airlines, and other service providers train and employ staff devoted specifically to perishables. In June 2012, for example, Lufthansa Cargo formed a dedicated team based at Perishable Center Frankfurt (PCF), Lufthansa’s major hub for perishables. PCF is a storage facility equipped with product-specific, temperature-regulated storage and processing capacity. The facility also offers freighter parking directly adjoining the facility to reduce time spent on the tarmac, where product is most likely to be exposed to warm temperatures and weather.

A Plum Job in Packaging

The biggest challenge in perishable logistics is "maintaining high-quality product and service levels," says van der Pluijm.

Proper packaging is essential to ensure perishables survive the hand-offs and temperature variability involved in air import and export. Packing strategies might include specialized boxes and packing materials, and use of gel packs, thermal blankets, dry ice, and other materials. Fresh fish is typically packed in polystyrene boxes with gel packs, for example.

Some goods need to be pre-cooled for transport to withstand flying conditions and extend shelf life. Hothouse peppers, for example, must be cooled from about 80°F down to 54°F.

One potential area for improvement is standardization of box sizes. In floral shipping, for example, large-headed roses require a different box size than carnations, and shippers sometimes specify a particular type of box, making it challenging to efficiently palletize shipments.

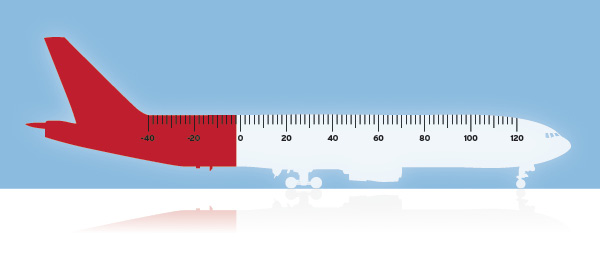

On freighters, perishable produce often moves via aluminum trays resembling cookie sheets, which are slid into pallets; on passenger aircraft, goods must be packed to fit into unit load device (ULD) containers that conform to the shape of the plane’s belly. When it comes to containers, airlines "have under-invested in consumable perishables and over-invested in pharmaceuticals," where they can charge higher fees, says Connell.

Another challenge is variability among ULD containers. "Depending on how and when they’re built, and whether they have been repaired, ULD containers can vary in weight," explains O’Neill. "Shippers want to maximize space capacity, but if they are five to 10 pounds over the weight limit, the airline can refuse the shipment or require them to remove product." Shipping loose boxes is much more costly per-pound than full containers. Packaging, gel packs, and ice also add weight, impacting margin.

For Gerawan Farming, which grows stone fruit and grapes in Fresno, Calif., under the Prima name, quality is a defining element of its brand. So the company designed its own single-layer cardboard container that offers 47 percent more strength than two-layer boxes. "We want to avoid jostling and bruises," explains Dan Cuevas, plant facility manager for Gerawan.

Keeping Tabs on Tomatoes

Like all shippers, perishables companies are seeking improved information on the location and condition of their precious cargo. That’s prompting carriers and logistics companies to beef up IT, enhance their portals, offer improved logger devices, and even develop their own mobile apps.

"The number of touchpoints is increasing, and shippers want to gather more data at those touchpoints," says Connell.

Shippers also typically want reports on temperature, humidity levels, and sun exposure. "The industry is struggling to find uniform metrics, so companies are establishing their own benchmarking," he adds.

Many seafood shippers want to be able to access their entire inventory as they’re selling. "They want to see exactly what products are available in real time, including whether the product was loaded on the plane, and its projected delivery time," says O’Neill.

Logistics providers are investing in meeting shippers’ visibility demands. Hellmann Perishable Logistics developed the Smart Visibility Tool, a sensor placed in the frame between the aircraft door and the container to monitor temperature, movement, location, and door openings—then communicate that information via GPS and satellite through the shipment’s journey.

Lufthansa Cargo unveiled a similar device in December 2013. Shippers can place a lightweight tracker in any consignment, track the shipment via a portal, and return the device by mail after the goods have been delivered. The transmitters switch off automatically during flight. Lufthansa is working to add sensors to the device to record conditions, in addition to location.

As long as consumers have an appetite for perishable products that can only be sourced in faraway destinations, air cargo will play a key role in the supply chain. But logistics professionals need to stay cool under the pressure of moving perishable goods quickly and safely through agile and flexible supply chains.

Blueberries in January?

Retailers have long sourced perishables from across the globe, but growing consumer incomes and appetites are driving the increasing diversification of produce markets, both as sources and destinations. Shoppers want more and better options, and they want them year-round.

In the United States, for example, blueberry availability was once confined to the North American growing seasons. But in the late 1980s, Chile began harvesting blueberries from October through late March, with much of the output going to North America. Peru and Argentina also produce berries for the U.S. market, and climate-controlled storage means the fruit is often available year-round. Similarly, in the United States’ off-season, peppers may come from Mexico, Israel, or Spain.

The FDA estimates 15 percent of the U.S. food supply is imported, including half of all fresh fruits, 20 percent of fresh vegetables, and 80 percent of seafood. Miami is a leading inbound port for produce and flowers; other major ports include Los Angeles, Houston, and Atlanta. Many outbound produce shipments export from California and Washington.

Globally, the rising middle class in locations such as China and India is seeking luxuries such as imported perishables. “The trend started with the Middle East 10 years ago,” says Jur de Graaf, general manager, export perishable logistics for Kuehne + Nagel, a global transportation and logistics company based in Switzerland. “Today, volumes are 10 to 20 times what they were then, and there is also a larger variety of produce, including strawberries, tomatoes, and peppers.” Population growth in general is also a factor.

Plant scientists have also devised ways to encourage better yields from plants, resulting in greater volume that can be sold into more markets.