Cold Chain Innovations: Turn Up the Chill

Smart sensing, monitoring, and packaging solutions keep temperature-sensitive shipments in the zone.

When a cold chain fails, good product turns into trash. That’s a big problem: 30 to 40% of food produced in developed countries is wasted before it even gets to market, estimates the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization. Faulty handling also may force shippers to discard critical healthcare commodities.

To keep cold products in great condition, shippers need to maintain freight at the right temperature in transit and in storage.

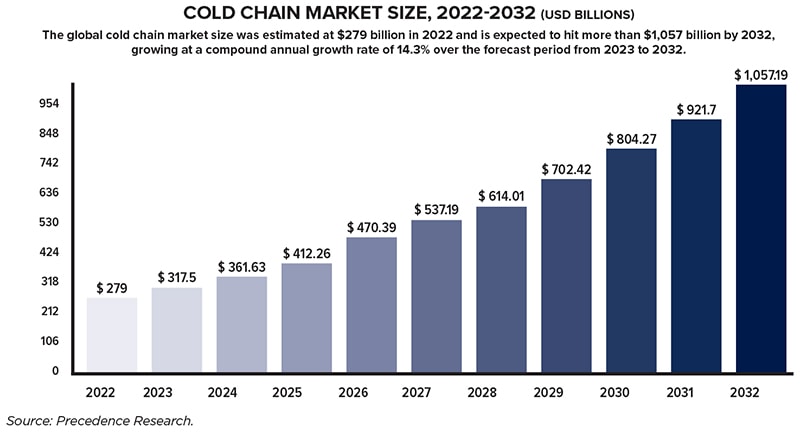

Demand for cold chain logistics services is growing. This market in the United States will see a compound annual growth rate of 15.9% from 2023 to 2032, predicts Precedence Research.

As more volume flows through the cold chain, technology developers are meeting the need with innovations in sensing, monitoring, packaging, and more. These solutions can help shippers maintain product integrity, reduce waste and, sometimes, minimize harm to the environment.

Warehouse Strategies

NewCold, a global food logistics provider based in Breda, the Netherlands, was responding to market changes when it opened a new, high-tech cold storage facility in Lebanon, Indiana in October 2023. These changes occurred as large, highly automated food processing companies came to dominate the market for processed foods.

Traditional cold storage facilities are too small and labor-dependent to fit the needs of those production giants, says Jonas Swarttouw, executive vice president, commercial and chairman of NewCold North America, in Chicago. Major food processors need warehouses that are big enough to create economies of scale and centrally located to support distribution throughout the United States.

NewCold developed the Lebanon facility in partnership with Conagra; the warehouse manages frozen foods for that company and one other large customer. The facility has 100,000 pallet positions, and work is underway to double that capacity.

NewCold has made special provisions to maintain temperature as product moves in and out. “All areas in the warehouse, including the dock, are frozen,” says Swarttouw, adding that nearly all other frozen food warehouses have docks that are refrigerated but not kept below the freezing point.

Robots and other automated systems do much of the physical work, driven by a material flow system, a warehouse management system, and a control system.

Like operators of most cold chain facilities, NewCold carefully monitors its cooling system. “The compression and the temperature technology are wired into the building management system,” says Matthew Staley, NewCold’s executive vice president, innovation and technology.

Alarms go off if the temperature strays outside the prescribed window.

Keeping it Tight

NewCold’s new highly automated cold storage facility in Lebanon, Indiana, is one of the largest cold storage facilities nationwide. The facility serves global food producers.

NewCold also takes care to use as little energy as possible for cooling. “We build the warehouse as a tight box where the only things going in and out are the pallets,” Staley says.

And it stacks those pallets densely, which helps them stay cold. NewCold says its facilities use 50% less energy than a traditional warehouse.

Leonard’s Express, a trucking company based in Farmington, New York, was also responding to market changes when it opened a 114,500-square-foot temperature-controlled warehouse in Shortsville, New York in late 2022. In this case, the evolution involved consumer habits.

“There are more temperature-controlled products being shipped everywhere now than there were 15 or 20 years ago,” says Ken Johnson, executive chairman of Leonard’s Express, whose fleet includes 700 refrigerated trailers.

Consumers buy more prepared meals these days. There’s also more variety within product categories, such as the many varieties of yogurt and plant-based milk in the dairy case.

That proliferation makes it harder to find refrigerated warehouse space. Leonard’s answered the need by building its new warehouse on spec. Customers stepped right up.

“We were hoping to be full within the first six months, and it was full a bit quicker than that,” Johnson says.

Frozen in Place

Leonard’s Express opened a 114,500-square-foot, state-of-the-art cold chain solutions warehouse in Shortsville, New York that allows shippers to track the temperature and location of their refrigerated loads from a smart device, 24/7/365.

The warehouse was designed to provide both refrigerated and frozen capacity, although due to market demand today, four of its five rooms currently store frozen foods.

Like NewCold, Leonard’s Express has made special provisions to keep product cold during loading and unloading, deploying dock doors that let workers open trailers inside the building. That space is cooled to a constant 34 F.

“There’s never an opportunity for warm air to get into the trailer,” Johnson notes.

The warehouse’s management system lets customers access data about their own products. “They know what room their product is in, so they can go into our system and look at the temperature if they have any concerns,” Johnson says.

“Some customers have internal auditing processes that require them to look at the temperature from time to time,” he adds.

Cold Freight in Transit

Courier Connection’s fleet is equipped with several different types of vehicles. Its refrigerated trucks measure 12 feet, and can accommodate any perishable foods or other commodities that require temperature-controlled transportation.

In an over-the-road trailer, one traditional monitoring strategy is to rely on technology built into the refrigeration unit. That’s what Atlanta-based Courier Connection generally does when distributors engage it to deliver food to customers in Georgia and neighboring states.

“We have the latest Freightliner trucks with the latest refrigeration units, which are some of the most robust and reliable,” says John Lauth, president of Courier Connection. The reefer units monitor themselves to make sure they maintain the correct temperature for the load in the trailer.

On long-distance runs, if the cooling unit detects a temperature anomaly it sets off an alarm to warn the driver. This doesn’t happen often. “But if we do have a problem, we move the load to one of our other refrigerated trucks as quickly as we can,” Lauth says.

To further reduce any risk to their food, some customers place a temperature monitor inside the load. “They can watch their food on an app to see if it gets above a certain temperature,” Lauth says.

If it does, then, unfortunately, they can’t sell it. But most of the time the freight arrives in good condition and gets transferred right away to a refrigerated room at the destination.

Some strategies for maintaining the cold chain are simply a matter of common sense. You need to keep the truck in good shape, verify that the door is shut after loading, and set the temperature correctly. Then follow smart procedures at the destination.

“Also make sure there’s somebody there to receive the freight before you open the door and let out the cold air,” Lauth says.

For shippers who want a closer view of chilled products in transit, Wiliot—based in Israel, with U.S. headquarters in San Diego—offers the ability to monitor temperature by the case or even by individual item.

Sensing as a Service

Wiliot’s “IoT pixels” enable a circular economy by allowing all reusable transport packaging such as crates, pallets, containers, and bins to continuously communicate their status. Food companies can then precisely track inventory, and monitor shipping and delivery.

Wiliot’s “sensing as a service” platform uses “IoT pixels”—devices about the size of postage stamps—to measure conditions such as temperature and humidity. The pixels don’t require batteries. They communicate via Bluetooth with inexpensive readers installed at various points throughout the cold chain, collecting data from product and transmitting it to Wiliot’s cloud-based platform.

Traditionally, a shipper might place a sensor in one or two spots within a refrigerated trailer, or ask a driver to insert a probe in the product now and then. Wiliot’s sensors, placed on pallets, cases, or individual units, give a more accurate picture of conditions, since temperature can vary greatly across small distances and over time.

“We were able to tell one customer that their fruit was being frozen not once but half a dozen times between the distribution center and the store,” says Steve Statler, chief marketing officer and ESG lead.

One grocery chain uses Wiliot’s system to track produce from field to store. This information helps the company, for example, make sure fruit that has been exposed to the most heat—and therefore is the ripest—goes onto store shelves first.

Wiliot provides application programming interfaces (APIs) to transmit data from the IoT pixels into applications used to monitor shipments.

“At the moment, our customers are some of the world’s largest companies; they tend to write their own apps,” Statler says. But smaller customers can incorporate the data into off-the-shelf software such as tracking solutions that are emerging in response to new food safety regulations.

Artificial Intelligence Instead of Probes

Another strategy for monitoring temperature in transit comes from EROAD, a New Zealand firm with a North American division based in San Diego.

EROAD’s CoreTemp system uses AI and proprietary algorithms to determine the actual temperature of product in transit without placing sensors on the freight.

EROAD developed CoreTemp at the request of trucking companies that no longer wanted to have their drivers stop periodically to insert probes in temperature-controlled products.

“Probes get lost,” says Dean Marris, the company’s chief data scientist. “Also, drivers are frustrated that they have to do this.”

Simulating Temperatures

To create custom algorithms, EROAD first develops a profile of the shipper’s most at-risk product, using highly accurate loggers to capture the load’s temperature at various locations in the trailer. Then data scientists use machine learning to determine what the temperature of the product would be in various situations, as temperatures measured by the refrigeration unit change over time.

These simulated temperatures provide a more accurate picture of how a load is faring in transit than a shipper could get just by tracking data from the refrigeration unit. For instance, a unit might register a spike in the temperature of the return air—air that the refrigeration unit pulls in to be cooled—when the trailer door is opened for a delivery. “But typically with the algorithms we develop, the temperature of the product changes a lot slower than what the return air will look like,” Marris says.

Companies currently using CoreTemp include Quality Custom Distribution, whose customers include Starbucks, Casey’s and 7-11.

Innovations in Packaging

While cold chains often rely on systems driven by electric power (called “active shippers”), for certain kinds of shipments, “passive” cooling is the norm. Passive cold chain packaging uses insulation plus a refrigerant, such as water ice, dry ice, or other chemical compound (known as a phase change material, or PCM) that absorbs heat as it melts and vaporizes.

Cold Chain Technologies (CCT) of Franklin, Massachusetts, provides passive thermal packaging for everything from pallet-sized loads to small parcels. Most of its customers ship life science products such as pharmaceuticals and biologics.

One major trend among these customers is concern about the environment. So, along with packaging for one-time use, CCT offers reusable thermal shippers, and shippers that can be recycled at the curbside. For example, Moderna’s COVID-19 vaccines in the United States were transported in reusable thermal containers from CCT.

Since many CCT customers ship high-value products, demand for visibility is growing as well. For example, if a delay occurs during travel, customers need to know how the temperature in the shipper is maintained.

“You want to monitor containers almost in real time, so you can prevent anything from happening and rescue the shipment,” says Amardeep Chahal, senior vice president, marketing and corporate development at CCT.

CCT works with numerous technology vendors, and with transportation companies such as UPS and FedEx, to provide tracking through its own web portal, CCT Smart Solutions.

The Case for Natural Refrigerants

The chemicals used for cooling in most refrigeration systems today—hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs)—have a massive carbon footprint. Their potential to warm the planet is many hundreds of times greater than the potential of carbon dioxide (CO2).

Since 2015, the not-for-profit North American Sustainable Refrigeration Council (NASRC), based in Mill Valley, California, has worked with food retailers, refrigeration manufacturers, and other stakeholders to encourage supermarkets to adopt refrigerants that do far less harm to the environment. Among these natural refrigerants, the top candidates are CO2, propane, and ammonia.

Refrigerants in supermarkets create pollution when gas leaks from the refrigeration systems. “Every grocery store has miles of piping and thousands of joints and valves, which makes the systems inherently leaky,” says Morgan Smith, program and communications director at the NASRC. “The average U.S. supermarket has an annual leak rate of about 25%.”

Switching to cleaner alternatives is no simple prospect. “Unfortunately, there are no very climate-friendly refrigerants that are drop-in solutions,” Smith says. A store would have to install an entirely new cooling system, which could shut the business for weeks and cost millions of dollars. As part of its work, the NASRC encourages governments to create financial incentives that make replacement projects more feasible.

Few stores have made the switch so far. But the NASRC is seeing progress. “When we were founded in 2015, the dialog was very different,” Smith says. “The industry as a whole wasn’t talking about natural refrigerants all that seriously.”

Now, policy makers are starting to focus on the problem. “That has done a lot to get the industry talking about natural refrigerants,” Smith adds.