Forming an Alliance with Ocean Shipping

After the 2016 Hanjin Shipping bankruptcy, carriers banded together to form alliances. Today, these alliances dominate ocean cargo shipping. Here’s how they affect your shipments and contracts.

Without ocean cargo, there would be rough seas ahead for the U.S. import-export business. Water is the leading international transportation mode in terms of both weight and value, according to the U.S. Department of Transportation’s Bureau of Transportation Statistics. In 2015, ships transported 71 percent of international trade weight and 48 percent of its value.

Freight Forwarder Or NVOCC?

Ocean Alliance Overview

But the ocean cargo waterfront changed for shippers earlier in 2017 when most major ocean carriers further consolidated from four alliances to three: 2M, Ocean Alliance, and THE Alliance (see sidebar).

While carrier alliances existed already, the new partnerships are more than the slot charter or vessel-sharing agreements of the past. “These alliances are much more proactive about planning what the future holds for members,” says Molly Bailey, director, international, for Transplace, a non-vessel-operating common carrier (NVOCC) based in Frisco, Texas. “It’s not just about how they can share getting cargo from Point A to Point B. There’s much more proactive thought going into how these carriers are collaborating.”

Today’s ocean alliances can be traced back several years to Maersk Line’s investment in a fleet of ships that were larger than any other carrier’s. Because the expanded capacity helped the company lower operating costs per container, it could reduce its rates. To remain competitive, other carriers followed suit with larger vessel purchases—which led to too much capacity in the marketplace. It became harder for carriers to remain profitable, as evidenced by the 2016 Hanjin Shipping Co. bankruptcy.

So carriers began banding together to manage capacity and routes. The current alliances now represent more than three-quarters of all global container capacity. The remaining volume is spread over niche operators serving smaller regions.

The impact of the new relationships on shippers remains to be seen, but some had to adjust when new partnerships forced alliances to change some lanes and ports served. “Shippers were tolerant of the changes and accepted that they had to find alternatives for certain lanes, even when contracts were in place,” Bailey says.

Those same changes have had an impact on timelines, too. “In some cases, transit times are longer because some ports are losing direct calls,” says Nerijus Poskus, vice president of global pricing and procurement at Flexport, a web-based freight forwarder headquartered in San Francisco.

For example, Portland, Oregon, generally doesn’t have enough cargo to fill the largest vessels, so freight destined for the city is often delivered to Seattle and transported to Portland by ground.

Capacity and Congestion

In addition, increased capacity and port congestion can cause delays. “Once freight moves to the level of a 22,000 TEU (20-foot equivalent unit) vessel, the time to unload at the port will increase,” says Vince Santinello, ocean business development and route manager, global forwarding, at C.H. Robinson, a Minnesota-based third-party logistics provider. “Having a chassis available for that freight also becomes an issue.”

Shippers can feel reassured that their carriers are less likely to repeat the Hanjin bankruptcy scenario, where container delivery was delayed for months in some cases, Bailey says.

“While it’s still to be determined, it seems that these carriers working together through alliances must trust that each partner is financially solid,” she says. A March 2017 announcement from THE Alliance reinforces that message, stating that the group has a contingency plan designed to protect shippers from risks associated with any participant carrier’s bankruptcy.

Getting on Track

The alliances offer greater potential for capacity management, according to Fauad Shariff, CEO of The CoLoadX Corporation, a New York company that provides a technology platform used by both freight forwarders and NVOCCs.

“The black hole of logistics has been tracking,” he says. “Partners have an opportunity to develop a unified tracking standard within the alliance that integrates with railroads and trucks, creating better access to information about container capacity at inland ports.”

To help shippers get the most from their relationships with the ocean alliances, experts recommend the following best practices:

- Spread cargo across all three alliances. “The ability to work across all alliances will be critical,” says Santinello.Bailey agrees, adding, “When negotiating rates and space, divide your business as equally as possible across all three alliances so you don’t have all your eggs in one basket.”

- Look for dedicated space allocations with specific carriers. An allocation is a commitment from the carrier that the space will be there when you need it.It’s a solution to a problem caused by a shipper’s ability to cancel a booked shipment, even at the last minute, without being penalized. That leaves the carrier with reserved space that is now empty. As a result, carriers overbook.

“It’s not unusual for an ocean carrier to book 100 percent more than it can transport,” Poskus says “If you don’t have an allocation, your cargo could get bumped.” Allocations are with carriers, not alliances, he adds.

- Pay attention to alliance partnerships on the ground. Because ocean carriers manage the inland portion of the cargo’s journey, too, alliance contracts with rail lines will determine how your cargo moves to its post-port destination. Contracts that fall outside of the shipper’s control will have an impact on cargo timelines.”Rail lines offer potentially different transit times,” cautions Poskus. “Some have better connection points than others, and some have on-dock rail while others don’t. Be certain to take all of this into account when making carrier decisions.”

- Revisit contract language. Deal with potential risks by addressing them in the contract.”In the past, a shipper’s biggest risk was predicting and locking in freight rates for the upcoming year,” says Cory Margand, co-founder and CEO of SimpliShip, a Rochester, New York, technology company that develops APIs—software-to-software connections—with companies such as Kuebix, a transportation management system provider. “The potential for carriers to change alliances and/or form new ones creates risks associated with capacity and port callings as well.”Because of the Hanjin bankruptcy crisis, Bailey has seen shippers now require that a certain percentage of cargo be moved on the carrier’s own vessels rather than those of others in the alliance. “It can give some peace of mind, but could cause logistical challenges or delays if a partner vessel is in the rotation when you need to ship,” she says.

Some shippers are adding contract language that allows them to negotiate to reduce the committed volume if the carrier’s performance metrics, such as on-time delivery, fall or the carrier changes direct port calls.

- Leave it to the experts. Managing ocean transportation can be a complicated, detail-oriented business. One carrier’s cut-off date for the port of loading on a certain day might be different from another carrier’s for the same day. Miss that cut-off and cargo sits for one week, waiting for the next sailing. Or, changing carriers at the last minute means you’ve got an empty container you can no longer use because it’s a different carrier’s asset.

Freight forwarders and NVOCCs are skilled at managing costs, meeting all cargo requirements, and guiding strategic decisions.

“We see more shippers working with freight forwarders and NVOCCs because they can make changes seamlessly,” says Margand. “The shipper, to a lesser extent, doesn’t have to deal with the problems that result from capacity or port changes. It’s the most efficient way to manage these risks.”

As ocean freight volumes continue to grow, implementing these and other best practices will lead to smooth sailing for both shippers and carriers.

Freight Forwarder Or NVOCC?

“There’s often confusion around the terms freight forwarder and non-vessel-operating common carrier or NVOCC,” says Fauad Shariff, CEO of The CoLoadX Corporation, which provides an ocean freight procurement platform for forwarders and NVOCCs.

To differentiate the terms, Shariff uses a travel analogy: The freight forwarder is like a travel agency but with a significantly higher value-added service offering, while the NVOCC is more like an airline consolidator that might offer freight forwarding services as well.

“NVOCCs make massive capacity commitments to carriers, so their job is to fulfill those commitments by re-selling that capacity to shippers or freight forwarders,” Shariff explains.

Here’s how the Federal Maritime Commission officially defines the terms.

An ocean freight forwarder:

- Arranges for cargo to move to an international destination.

- Dispatches shipments from the United States via common carriers, and books or arranges space for those shipments on behalf of its shipper customers.

- Handles the documentation and performs related activities for those shipments.

- Must be licensed and provide proof of financial responsibility for paying any claims generated by the transportation-related activities.

An NVOCC:

- Is a common carrier that provides ocean transportation, issues its own house bill of lading, and doesn’t operate the vessels providing the transportation.

- Acts as a shipper in its relationship with the vessel-operating carrier moving the cargo.

- Must be licensed and provide proof of financial responsibility for paying any claims generated by the transportation-related activities.

- Must publish a tariff and apply for an ocean transportation intermediary license.

One big advantage of working with NVOCCs is that they can consolidate smaller shipments to form a containerload. “This is a significant value-add for many less-than-containerload shippers,” Shariff says.

Ocean Alliance Overview

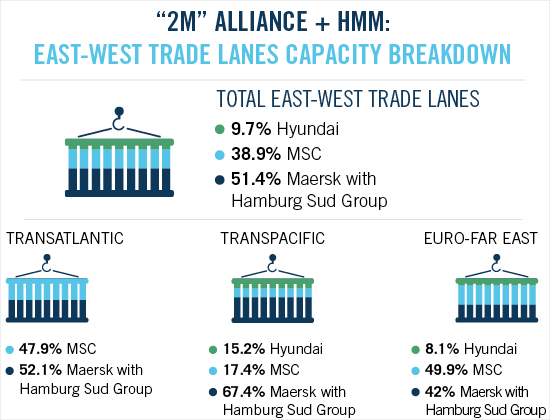

On April 1, 2017, major ocean carriers further consolidated from four alliances to three that now represent more than three-quarters of all global container capacity. Here are the essentials based on information provided by the alliances.

2M Alliance Partners

Partners:

Maersk Line and Mediterranean Shipping Company (MSC), with a three-year strategic cooperation agreement with Hyundai Merchant Marine (HMM) and a slot purchase agreement with Hamburg Süd.

Overview:

The 2M Alliance was formed in 2014 with a 10-year vessel-sharing agreement between Maersk and MSC on the Asia-Europe, Transatlantic, and Transpacific trades. HMM and Hamburg Süd signed on in early 2017.

“2M has run stable for almost three years and is the only alliance not to undergo major structural changes in 2017,” says Mikkel Elbek Linnet, Maersk press officer.

Trades:

- Transpacific: 13 loops, 41 ports

- Transatlantic: 7 loops, 29 ports

- Asia—Europe: 6 loops, 29 ports

- Asia—Mediterranean: 4 loops, 36 ports

Source: Flexport.

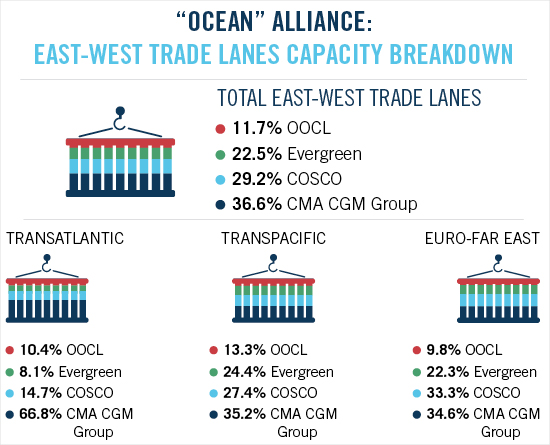

Ocean Alliance

Partners:

CMA CGM Group, COSCO Container Lines, Evergreen Line, and Orient Overseas Container Line (OOCL).

Overview:

Providing 40 services on the East-West trades with approximately 100 ports of call and almost 500 port pairs, the Ocean Alliance operates a fleet of nearly 350 vessels with about 3.5 million TEUs in total capacity. As the main contributor, the CMA CGM Group has the largest capacity share within the alliance—35 percent—deploying a fleet of 119 vessels.

“This new offering is a cornerstone of our strategy as it reinforces our competitiveness and strengthens our position as a key player in the shipping industry,” says Rodolphe Saadé, CMA CGM Group vice chairman.

Trades:

- Transpacific: 20 loops, 52 ports

- Asia—Northern Europe: 6 loops, 31 ports

- Transatlantic: 3 loops, 21 ports

- Asia—Mediterranean: 4 loops, 33 ports

- Asia—Red Sea: 2 loops, 12 ports.

- Asia—Middle East: 5 loops, 25 ports

Source: Flexport.

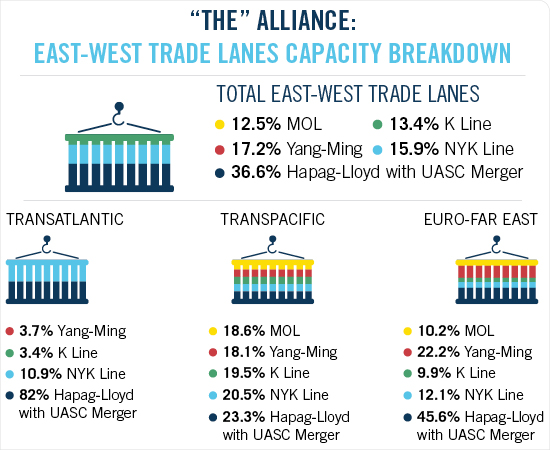

THE Alliance

Partners:

Hapag-Lloyd, Nippon Yusen Kaisha Line (NYK), Mitsui O.S.K. Lines (MOL), “K” Line, and Yang Ming Line.

Overview:

The largest member, Hapag-Lloyd, is joined by three Japanese carriers and the Taiwanese Yang Ming Line. Using 240 vessels, the group offers 32 services in three trades: the Far East, North Atlantic, and Transpacific. The alliance makes it possible for the Hapag-Lloyd network to be better connected to the Middle East through four Red Sea and Arabian Gulf services. Ships deployed include the MOL Triumph, the largest containership in the world. It measures 400 meters long, almost 59 meters wide, and has a capacity of 20,170 TEUs.

In March 2017, alliance members announced a contingency plan designed to protect shippers from risks associated with a participant carrier’s bankruptcy.

“Customers’ reaction to the Hanjin incident showed a clear demand for such a safety net and the partners of THE Alliance are proud to present the first contingency plan of its kind in liner shipping,” says Monika Gabler, Hapag-Lloyd AG press officer.

Trades:

- Asia—North Europe: 5 loops, 33 ports

- Asia—Mediterranean: 3 loops, 23 ports

- Asia—Middle East: 1 loop, 11 ports

- Transpacific—West Coast: 11 loops, 18 ports

- Transpacific—East Coast (via Panama and Suez): 5 loops, 33 ports

- Transatlantic: 7 loops, 35 ports

Source: Flexport.