Southeast Ports: What’s on the Horizon?

Looking out to 2015, anticipation is swirling about the Panama Canal’s expansion and impact on U.S. trade. Among southeastern ports and shippers, that wave of anticipation has already made landfall.

In a 2006 national referendum, voters in Panama overwhelmingly approved plans to expand its Canal—an effort that will construct a deeper and wider third set of locks, and double capacity through the century-old gateway. The vote set in motion a publicity machine that has been working in overdrive ever since.

Memorandums of understanding between the Panama Canal and U.S. port authorities stoked anticipation and excitement. Then, as construction commenced and images of dry excavations began circulating, the celebratory smoke gave way to a clearer picture of what the expansion project might mean for global trade.

Today, less than three years from completion, alarm bells are ringing as port authorities seek to secure last-minute funding, enhance infrastructure, and fine-tune existing operations. Shippers and consignees are similarly evaluating their supply chain networks and investing in new distribution centers (DCs) to capitalize on the economies of larger New Panamax vessels.

As the Panama Canal expansion deadline looms, the U.S. transportation and logistics sector anxiously awaits that first surge of Asian-origin containers. But in the U.S. Southeast, that swell of anticipation has already arrived.

The 2002 West Coast port strike shut down trade for 10 days in October during the peak holiday shipping season. Many companies lost money, recalls John Wheeler, director of trade development for the Georgia Ports Authority.

“The strike created an undeniable paradigm shift from West Coast intermodal to direct discharge at East Coast ports, closer to consuming population centers,” he says.

Then, in 2005, congestion became another concern as West Coast ports struggled to handle the volume of Asian-origin containers flooding terminals. For the Georgia Ports Authority and others it meant record growth. “Georgia’s ports averaged 11.5- percent container growth annually over the past decade,” adds Wheeler.

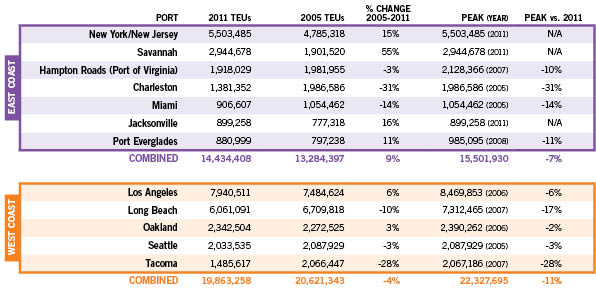

To put this in perspective, consider the current hierarchy of U.S. ports. Los Angeles and Long Beach remain the top two gateways for North American container traffic, followed by New York/New Jersey and Savannah, according to the American Association of Port Authorities’ (AAPA) 2011 rankings. The West Coast still overwhelmingly drives capacity.

But breaking down ports by geography reveals a telling sign. Five West Coast ports—Los Angeles, Long Beach, Oakland, Seattle, and Tacoma—rank among the top 20 container gateways in North America. The U.S. Southeast has six in the top 20—Savannah, Hampton Roads, Charleston, Miami, Jacksonville, and Port Everglades.

After most ports hit record container peaks between 2005 and 2008, the bottom dropped out of the market during the recession. Only now is the industry showing signs of recovery (see chart, below).

In fact, the East Coast’s two largest ports hit their container peaks in 2011. Savannah hasn’t slowed down, adding more than one million TEUs over the past seven years at a remarkable 55-percent growth in container throughput. So, too, has Jacksonville. New York/New Jersey and Port Everglades also recorded marked gains.

On the U.S. West Coast, it’s a different story. Los Angeles gained back some market share after topping out at 8.5 million TEUs in 2006, and both Oakland and Seattle have kept pace with their peak volumes. Long Beach and Tacoma, however, experienced noticeable drop-offs.

This cannibalization of West Coast container volume is expected to continue as the charter date for the Panama Canal’s expansion nears and Southeast ports head for a dead reckoning with New Panamax vessels capable of ferrying 10,000-plus TEUs in a single calling.

But a more compelling factor is the sheer pace of development in the Southeast. It’s arguably the fastest-growing region in the country—comparable to western states such as Arizona and Utah—but its population density is far greater. Forty-four percent of Americans reside in the Southeast, and that number is growing.

Florida is the poster child for population growth. It’s the fourth-largest state economy by GDP, and the population is expected to reach 23 million by 2020. More importantly, “Eighty-one million people visit Florida every year; it is truly a consuming state,” says James Hertwig, president and CEO of Jacksonville-based Florida East Coast (FEC) Railway.

A population boom and gantry crane booms stretching farther than ever act as welcome signs for ports and retailers. Many are reconsidering global sourcing strategies and domestic distribution networks as they look to capitalize on the Southeast’s fast-changing port complexion.

Ace Hardware Bets on Virginia

In July 2012, Oak Brook, Ill.-based Ace Hardware opened a 336,000-square-foot import redistribution center (RDC) in Suffolk, Va. As the first tenant to settle into the 900-acre CenterPoint Intermodal Center, which will eventually feature more than 5.8 million square feet of industrial space, the home improvement chain is counting on this new facility to become an important cog in its U.S. supply chain.

Currently, Ace Hardware operates 14 retail support centers (RSCs) and two RDCs—the second in Kent, Wash. The Suffolk facility specifically supplies eight support centers in New York, Virginia, Ohio, Georgia, Alabama, Florida, Arkansas, and Texas. The Kent RDC services the remaining six centers that stretch west from Illinois.

“Prior to the Suffolk facility, our Kent facility handled the majority of import product,” says Tim Duval, supply chain director at Ace Hardware. “The Suffolk RDC cuts our transportation cost to RSCs, while also cutting overall transit time and reducing inland transit times for product held in the facility.”

Most freight coming through the Suffolk operation originates in Asia and moves all-water to the Port of Virginia. The decision to locate near the port was predicated in part by the Panama Canal’s expansion and larger vessels calling on the port.

“We investigated several cities on the Gulf and East Coasts to find the ideal location to allow us to reduce costs and provide optimum service to our retailers. Suffolk is only 30 miles from the Port of Virginia,” says Lori Bossmann, senior vice president, supply chain and retail support, Ace Hardware. “We also have the capability to expand our new facility up to 500,000 square feet to accommodate growth.”

The Port of Virginia—which features facilities in Hampton Roads, Norfolk, and Portsmouth—is already well-equipped to manage the expected container volume surge. At 50 feet, it is one of only two ports on the U.S. East Coast (the other is Baltimore) currently capable of accommodating 10,000-plus TEU vessels. About 30 international steamship lines service the port, and both Norfolk Southern and CSX offer on-dock, double-stacked intermodal service inland.

Continuing development of the Heartland Corridor, a $150-million public-private partnership between Norfolk Southern and the Federal Highway Administration, will increase intermodal capacity and facilitate freight movement between Virginia; Columbus, Ohio; and Chicago. Rail accessibility also played a role in Ace Hardware’s Suffolk site selection decision.

“Approximately 15 percent of our freight moves via intermodal,” says Duval. “We take that into consideration for any operation we look at.

“Each year, we engage our carriers in a Request for Proposal (RFP) process, and consider the transportation mode per lane in the overall analysis, along with cost and the effect on inventory levels,” he adds. “Having intermodal availability as an option at the Suffolk facility provides us with greater choices during the RFP process.”

Optimizing Port Operations

With infrastructure on solid footing, the Port of Virginia is now looking to optimize existing operations in anticipation of future growth. For example, intermodal chassis management has become a terminal concern after the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration (FMCSA) began enforcing its “Roadability Rule” in 2009 and 2010. The mandate places more responsibility on chassis owners and trucking companies to properly inspect and maintain roadworthy equipment. Many steamship lines, which historically have supplied their own chassis, swiftly exited the business following the FMCSA’s ruling, casting uncertainty on how ports and shippers would manage this void moving forward.

The Port of Virginia, by contrast, has operated its own chassis pool with a third-party partner for eight years—a consequence of wanting to free up on-site space and help truckers expedite turns.

“Some of our old aerial photos show a huge swath of land dedicated to chassis. It’s remarkable the amount of productive space we were losing,” says Joe Harris, spokesperson for the Port of Virginia. “Now we stack chassis vertically in a one-acre corral. Truckers drive in from one side, chassis stackers unload units and put them on the ground, drivers back up and pick out the 20- or 40-footers they need, then exit the other side. We ensure roadability for all chassis.”

The Port of Virginia expects to continue tweaking its pool, but doesn’t anticipate any problems some other gateways are just beginning to encounter. In fact, its chassis program has had a marked impact on terminal efficiency and asset utilization. Before the port started the equipment pool, about 22,500 chassis were on terminal. Today, that number is 11,300. “In terms of freight, we doubled volume on half the number of chassis,” says Harris.

Elsewhere, the Port of Virginia is conducting a holistic review of its operations as part of a multi-year project with the Global Institute of Logistics—a membership organization for global port communities founded by the late Robert Delaney—to pursue total quality port certification.

“The review analyzes every step a unit of cargo takes through the Virginia Port system to find out how efficient it is,” Harris explains.

The objective is to guarantee specific service and performance standards that are continuously benchmarked and measured, much like ISO standards. Eventually, the port will extend this review to its Richmond inland facility, and include barge service as well as rail/intermodal jumps.

IKEA Finds Balance in Savannah

As the fourth-largest containerport in the United States, Savannah increased volume more than any other major U.S. port over the past seven years—and it shows. It has attracted big-box retailers the likes of Lowes, Home Depot, Dollar Tree, Walmart, and Target.

In 2007, Swedish home furnishings retailer IKEA opened a 785,000-square-foot (with potential to expand to 1.7 million square feet) distribution facility at the Savannah River International Trade Park. Accessibility to the Southeast market’s future store openings and proximity to the port were important factors in the site selection. IKEA’s DC is located four miles from Savannah’s Garden City Terminal.

“When we evaluated locations for a southeastern DC, we saw the potential for expansion in Savannah—from the port’s perspective, as well as our own. We have the opportunity to double our size here,” says Joseph Roth, IKEA’s director of public affairs.

IKEA opened the Savannah DC to serve retail locations in Atlanta, Dallas, Houston, and Round Rock, Texas, which was then under construction. Five years later, it opened three stores in Florida and one in Charlotte—all supported by the Savannah distribution operation.

Since 2007, IKEA has gradually expanded its U.S. distribution footprint to match the growing presence of retail sites throughout the country. It recently opened a DC in Tacoma, Wash., to replace a leased facility in Vancouver, B.C. Together with an existing facility in Tejon, Calif., the DC serves West Coast store locations. IKEA also consolidated a leased DC in Bristol, Pa., into its larger Perryville, Md., operation. All told, the company will have six U.S. distribution centers (including Westhampton, N.J.) when it eventually brings a new Midwestern hub on line in Joliet, Ill.

Like the aesthetics of the products it sells, IKEA’s distribution design is discreet, balanced, and easy to put together. The company values regional DCs near major ports of call and in areas with existing and future demand. While the majority of its product is manufactured in Europe, volume also comes from Asia and, increasingly, U.S. suppliers.

All Asia-origin freight moves through either Tacoma or Tejon, so the Panama Canal has had little influence on supply chain machinations to date. Still, Roth acknowledges, “if issues arose with West Coast ports, such as the strike in 2002, the Panama Canal could be an alternative if we had to move goods from Asia to the East Coast. Our network is flexible enough to do that.”

That says a lot. In 2002, many U.S. consignees importing Asian freight to the West Coast had little recourse when labor strife hit the ports, delaying shipments and orders. IKEA’s current network, with established DCs in all four corners of the United States, guarantees faster speed-to-market times while creating necessary flexibility and contingency options if and when exceptions occur.

While the Panama Canal is a blip on the horizon for IKEA, it understands that supply chain partners have a stake in what’s going on. “We focus on port expansion efforts where we operate,” says Roth. “Savannah is in the process of finalizing dredge plans, and we support that.”

A Port for All Trades

The Port of Savannah’s harbor deepening project is already underway, with work scheduled to begin in the fourth quarter of 2012. The four-year process to dredge Savannah’s channel to 47 feet will follow the completion of the Panama Canal’s expansion project—a reality that obscures what’s already happening, says John Wheeler.

“A cascade of larger vessels is already coming to the U.S. East Coast today via the Suez Canal,” he notes. “When 14,000-TEU ships come into service, the steamship lines have to do something with their 8,000-TEU vessels. The second largest trade lane in the world is Asia to the United States, and we’re seeing those ships right now.”

The Mediterranean Shipping Company (MSC) recently added Savannah to its Golden Gate service originating in Shanghai. The service transits the Suez and utilizes ships in excess of 9,000 TEUs. The string also includes New York/New Jersey, Norfolk, Baltimore, and Charleston.

Savannah’s stature as a logistics hub played a large role in MSC’s decision to add the port to its rotation—particularly because so many proprietary beneficial cargo owners and distribution centers are located in the area.

A few years ago, the thinking was that an East Coast surge would have to wait until the Panama Canal expanded, says Wheeler, but that has gone by the wayside. Rather, an evolution in supply chain strategy has been happening for some time.

“Transit time isn’t as important any more; cost is,” Wheeler explains. “Big-box retailers want the best rates. And shipping lines want their costs to be as low as possible, too, so they are migrating to larger vessels. An 8,000-TEU ship is a 40-percent savings per slot over a 4,500-TEU ship.

“Even though transit times may be longer, shippers are migrating toward larger vessels because it’s cheaper,” he adds. “And all carriers are moving to slow steaming due to the high price of bunker fuel.”

The easy solution for many ocean carriers is to put the smaller containerships on the Suez route. Newer, larger vessels will service the Panama Canal when that volume spikes. East Coast ports have an existing value proposition for attracting more Suez trade.

“Total capacity from Asia to the U.S. East Coast via the Panama Canal is 64,360 TEUs per week. By comparison, transits via the Suez Canal account for 55,496 TEUs per week,” says Wheeler. “That’s closer to a 50/50 percentage than you might think. Seven years ago, that balance would have heavily favored the Panama Canal.”

Even if transit times are less important because of better supply chain visibility and demand forecasting, transportation connectivity and intermodal efficiency have conversely grown in significance. Regardless of where ports are pulling container volumes from, U.S. distribution follows a more predictable course.

Savannah is keeping ahead of the demand curve in terms of transportation accessibility in and out of its terminals. The port is 10 minutes from both I-16 and I-95, and offers on-dock rail/intermodal service with Norfolk Southern and CSX.

“A container can be off the ship on Monday, at the intermodal yard that night, and on its way to destination Tuesday morning,” Wheeler says. “It’s cheap and quick because it’s right here at our facility.”

Florida’s New Reckoning

While Virginia and Savannah have solidified their reputations as key gateways to the Southeast—with intermodal inroads into the U.S. heartland—Florida’s container ports have predominantly served the Florida market. Given the state’s population density and tourism industry alone, that could be a positive.

But 45 percent of containers consumed in Florida come through non-Florida ports, according to research by economic consultant John Martin in collaboration with Port Miami. That figure jumps to 52 percent for Asian-origin containers—despite the fact that Miami handles much of that cargo already. A large volume of this freight moves West Coast intermodal or through Savannah, which creates low-hanging fruit ripe for picking, according to Martin.

With the Panama Canal expansion, Port Everglades and Port Miami have interest in capturing Asia-to-U.S. East Coast container traffic. Because both ports are strong Latin American gateways, transshipment potential abounds. New Panamax vessels will only feed that demand.

Ideally, when a 10,000-TEU ship comes into Miami or Port Everglades direct from Asia through the Panama Canal, it will unload shipments for the U.S. and local Miami market, and for transshipment south, then turn around.

“The large ships can’t call multiple ports. Carriers lose all economies of scale once they start doing milk runs,” says Martin. “The advantage of operating bigger ships is that savings occur on a line-haul basis. Capital costs are high, so carriers must keep vessels deployed all the time.”

Miami already participates in the Asia trade as a first U.S. inbound port of call. But larger vessels, fully laden, will naturally attract further transshipment activity. The most important requisite is having a 50-foot-deep harbor capable of accommodating these ships. This is also a consideration for export trade. As a last outbound call, ports with sufficiently deep berths can siphon more cargo from other ports that have draft restrictions.

The challenge for Port Everglades and Port Miami is to make South Florida a viable distribution hub for the Southeast market—not just an entry point for Florida-consumed goods, a gateway to Latin America, or a destination for cruise ships. Florida East Coast Railway will play a big role in making this objective a reality.

Jim Hertwig, who joined FEC in 2010 after serving in a similar capacity at CSX Intermodal, also brought with him 30-plus years of working exclusively on the trucking side. So he understands the importance of rail/intermodal service and how FEC can compete against, and partner with, the trucking industry to help make Florida’s transportation system more competitive. For Port Everglades and Port Miami, this is a game changer.

FEC “owns” Florida’s Atlantic coast, and it’s the most direct means of transporting freight to and from the state’s growing ports and broader southeastern region. In fact, 100 percent of CSX and Norfolk Southern intermodal business going to South Florida comes to FEC in Jacksonville.

Unlike most Class 1 railroads that haul unit trains, FEC’s freight mix is varied. Durable concrete-tied mainline track, relatively flat terrain, and consistent speeds running well below capacity make transport reliable and efficient. It can run automobiles, carloads, and intermodal containers all day on the same tracks, and still make intermodal scheduled delivery times.

Keeping the Trains Running

“One competitive advantage of multiple intermodal departures in each direction is surface lead time,” notes Mark Yoshimura, vice president logistics-transportation for FEC. “If a beneficial cargo owner or shipper can’t make that first cutoff time, additional trains are still running that can usually make it to the destination in time to meet local deliveries—especially competing against truck.”

In addition to its carload and intermodal container rail business, FEC’s owner-operator highway services division delivers door-to-door throughout Florida and beyond. Several dedicated intermodal services connect South Florida to markets as far afield as Atlanta, Chicago, and New York/New Jersey. Also, recognizing that the railroad can only pull in a finite amount of business, FEC is working with trucking companies to populate the system with more freight.

“The high number of DCs in Savannah creates an abundance of outbound loads,” explains Hertwig. “We set up a drop lot in Savannah where truckers can unhitch a unit, pick up an empty, and make a pick-up, thereby reducing deadhead miles.

“From Savannah, we connect with our train in Jacksonville, which continues on to South Florida,” he continues. “It’s an overnight service.”

Additionally, smaller motor freight carriers bring units into Jacksonville and FEC ferries them to South Florida via rail, makes the deliveries, then returns the empties. They use the railroad’s yard as their own de facto terminal.

This type of flexibility and efficiency has attracted a slew of customers, including Seaboard Marine, UPS, and Walmart. The big-box retailer operates a DC six miles from FEC’s Fort Pierce ramp, and works directly with the railroad.

“Walmart’s private fleet drivers bring units out of the system in Jacksonville, and FEC runs them to Fort Pierce and back,” says Hertwig. “People will say you can’t do short-haul intermodal. But I’ll tell you we do—147 miles with Walmart.”

FEC’s capabilities are a big reason why South Florida ports are bullish about their chances of competing for Asian-origin container volume when the Panama Canal expansion is complete. But there’s also a measure of reciprocity. FEC is equally dependent on Port Everglades and Port Miami to execute their expansion plans, and bring more freight into the pipeline. Currently, southbound and northbound container volume runs at a 4:1 ratio. FEC and the ports hope that will balance out.

Miami is in the process of completing three major projects: a $915-million Port of Miami Tunnel to provide a direct connection between the port and the interstate, while reducing congestion downtown; a $225-million harbor-deepening project; and a $23-million TIGER II grant with FEC to rehab track, build sidings, reconstruct a bridge into the port, and upgrade downtown intersections. When complete, FEC’s on-dock rail/intermodal presence will feature three 3,000-foot spurs capable of pulling half-mile trains in and out of the port.

Port Everglades is making similar efforts to optimize and expand its terminal capacity. A $120-million channel deepening and widening project is in the works, and should be complete by 2017, says Steven Cernak, director of Port Everglades.

The $321-million Southport Turning Notch expansion will lengthen the existing deepwater turning area for steamship lines from 900 feet to 2,400 feet, providing five additional cargo berths.

This project is important because, while ports can manage shallower drafts by partially loading ships—as Port Everglades currently does—there’s nothing they can do about vessel size. As part of this effort, which will eliminate 8.7 acres of a mangrove conservation easement, the port is enhancing 16.5 acres nearby with 50,000 new mangroves and plants.

Finally, Port Everglades is building a $72-million intermodal container transfer facility (ICTF) as part of a public-private partnership with FEC.

“The ICTF will process domestic and international intermodal containers, as well as eliminate highway drayage and reduce congestion,” says Cernak. “The ICTF will help improve throughput by getting freight in and out of the port more easily.”

In addition to its collaboration with Port Everglades and Miami, FEC is making its own investments. Flagler, a real estate affiliate of the railroad, is developing the South Florida Logistics Center, a 400-acre complex adjacent to the Miami International Airport at FEC’s Hialeah railyard. The plan is to create a multi-use warehouse environment that connects all transport modes in the area.

All these developments at the ports and on the rail feed one succinct value proposition that Hertwig believes will favor Florida in the long run. “By the time a ship gets up the river to Savannah, we’ll have the cargo at its destination,” he says.

A New Panamax Horizon

On March 1, 2012, the Port of Virginia bid adieu to the 9,178-TEU capacity MSC Roma, a vessel deployed on the steamship line’s Golden Gate service. The ship was so heavy it required 48.5 feet of draft—a high water mark for East Coast ports.

The occasion offers a sign of things to come, as well as a reminder of ports recently passed. Savannah welcomed the MSC Roma in February 2012, one month earlier, but it was partially loaded and on an incoming tide. On this latest turn, the Port of Virginia was the vessel’s final U.S. outbound call.

Emerging rivalries among East Coast ports is good for business. A “draft race” is clearly unfolding as ports aim to stack decks higher and faster than their peers. Intermodal connectivity will also be a competitive differentiator.

In the Southeast, the stakes are higher, given the growing consumer demand that is up for grabs. Established container ports such as Savannah and Virginia face new competition in Florida. The Panama Canal expansion will open up Asian trade, and sophisticated supply chains that can account for longer transit times will likely test all-water sailings to the U.S. East Coast if they can reduce total logistics costs.

Other variables are at play. The Caribbean and Latin America are emerging nearshore locations for U.S. manufacturing and sourcing. Eastern Europe is still considered a future offshore target, and Africa will eventually follow suit. East Coast ports are positioned for sustained growth from one direction or another.

But all these considerations can’t obscure the reality that the U.S. West Coast still dominates the container trade. And China isn’t going anywhere. Los Angeles and Long Beach have market share, and intermodal landbridge transit times from west to east are generally faster and more competitive. The extent to which the Panama Canal expansion impacts Asian-origin transportation routings and carrier rates—both on the ocean and trucking side—remains to be seen.

West Coast ports, too, may find new transshipment opportunities into Latin America. And if U.S. manufacturing makes a rebound, they will be well-positioned to feed Asia’s growing consumer base while turning full containers.

One certainty is that the next few years will be an exciting time for the East Coast port industry, and the Southeast specifically. Development will be rampant and rapid. Shippers and consignees—especially retailers—will be keeping tabs as they consider their own future growth initiatives.

Panama Canal chatter has been building for six years. The Asia-U.S. East Coast dialog has lingered even longer.

Coming soon in 2015 will be a cathartic ending to a script that has everyone buzzing in anticipation.

The Seven-Year Switch

Even as the pull of New Panamax capacity draws interest and investment to Southeastern ports, West Coast intermodal transportation is still the go-to route for most Asian-origin container volume. In some cases, even importers that have tested all-water routings from Asia to the U.S. East Coast still prefer the U.S. landbridge option.

In 2005, high-end patio furniture importer Summer Classics was working with Averitt Express International to manage Asian-origin shipments, some of which were transiting the Panama Canal.

The Montevallo, Ala.-based company supplies U.S. dealers and retail outlets including Brookstone, Home Depot, Crate & Barrel, and Neiman Marcus. It also has a retail presence in the Southeast.

At the time, Summer Classics was transshipping freight through the West Coast ports of Long Beach, Los Angeles, and Tacoma. Closer to home, it made arrangements with some Florida customers to take direct container shipments from Asia through the Canal. Summer Classics also had freight coming into the Port of Charleston that moved by rail to Atlanta, and was then drayed to Birmingham.

With West Coast port congestion an emerging concern, and because Summer Classics was controlling inbound transportation from Asia through its third-party partner Averitt, it had the flexibility to reroute shipments accordingly.

Fast-forward seven years, and Summer Classics’ sourcing and distribution footprint has changed considerably. The importer still works with Averitt as its sole logistics provider, but the nature of its transportation and distribution network has evolved.

“We are bringing in roughly 800 to 900 containers per year now, compared to 350 in 2005, and opened a 45,000-square-foot distribution center in Los Angeles,” says Andy Kennedy, logistics manager, Summer Classics. “We bring all containers through Long Beach to our DC.”

The company still direct-ships containers to East Coast customers via the Panama Canal—anywhere from 50 to 100 containers per year—but not nearly as many since the 2008 economic downturn.

“We had a good thing going for a while, bringing containers into the Port of Mobile. But service times eventually lengthened and our carrier of choice pulled out vessels,” Kennedy says. “The current problem with going all-water to the East Coast is the outrageous end-drayage cost to Alabama. If fuel prices continue to drop, we may change the way we bring in some containers. But currently, all freight will go West Coast, then on to Alabama.”