Full Circle: Reverse Logistics Keeps Products Green to the End

Smart strategies to reuse, refurbish, and recycle products and raw materials not only benefit the environment, but also save money and increase profits.

Adding Up Green Gains

Case Study: Philips Consumer Lifestyle

Reverse Resources

While companies struggle at times to find ways to make their supply chains more environmentally friendly, one subset of the supply chain stands out as inherently green: reverse logistics. Because reverse logistics by definition includes processes such as remanufacturing, refurbishment, recycling, reuse, and asset recovery, engaging in reverse logistics activities guarantees companies a certain level of green.

“All elements of reverse logistics have green implications,” says Jeff Robe, director of marketing for the Reverse Logistics Association (RLA), a trade organization focused on educating retailers, manufacturers, and third-party logistics providers about the benefits of reverse logistics. “Reverse logistics addresses questions including: At a product’s end of life, can some components be salvaged and reused? Can the materials be ground up, recycled, and made into additional parts?

“Recovering products, refurbishing goods, and pulling out parts such as precious metals that can be recycled or reused are green processes, and they bring a huge benefit to the environment,” he adds.

Through effective reverse logistics operations, companies can also cut out inefficient returns processes that result in unnecessary transportation moves, helping to reduce carbon emissions and improve air quality. It is hard to argue against that list of green attributes. But environmental green is only feasible if it doesn’t cost too much of the other kind of green.

Contrary to what some logistics professionals suspect, it is possible to manage reverse logistics processes so they are friendly to both the environment and the bottom line.

Good for the Bottom Line, Too

The benefit reverse logistics brings to companies ranges from three to 15 percent of the overall bottom line, according to RLA estimates. Robe cites electronics giant Cisco as a prime example. Partnering with a third-party provider and revamping its reverse logistics processes turned the company’s reverse logistics function from a cost center to a profit source. What was an $8-million loss for Cisco in 2005 became a $147-million revenue generator by 2009, according to Rehman Mohammed, Cisco’s senior director, customer value chain management.

Another example of green reverse logistics contributing to the bottom line is mobile electronics producer Palm Inc. The company revamped its reverse logistics processes to focus on refurbishing its goods, and now resells them using secondary channels such as an online corporate store and Internet retailer Overstock.com. Refurbishing the returned inventory for consumers, rather than leaving it to be scrapped, benefits the environment and Palm’s profitability.

Thanks to the revamp, Palm decreased processing costs by 50 percent, reduced returned goods inventory to less than two weeks, and tripled the product recovery rate. “Now we are often able to receive up to 80 percent of the retail sales price for our returned goods,” says Dawn Wang, senior manager of reverse logistics at Palm.

Sometimes, finding a way to make green reverse logistics pay off is just a matter of looking beyond short-term profit motives to long-term business and environmental gains.

“Businesses would not implement green reverse programs if they did not ultimately reflect a bottom-line value,” says Dave Meyer, vice president of sustainability consulting firm Sustainable Economic & Environmental Development Solutions (SEEDS) of Vancouver, Wash. “Companies get hung up focusing on short-term horizons instead of a long-term complete product lifecycle perspective,” he says, explaining that the initial capital and process reengineering costs sometimes involved in green reverse logistics may scare companies away.

“Companies need to consider collaborative opportunities within their supply chain and their long-term ROI,” Meyer says. “They should also weigh the intangible benefits of being green, such as positive public relations and consumer loyalty.”

But it’s simpler than that. The very goal of reverse logistics, and what makes it green, is also what makes it smart from an economic perspective: getting rid of waste, which is costly to profits and harmful to the planet.

“The whole idea of reverse logistics is to reduce what is used to manufacture a product; reuse components that can be economically recovered, for as long as possible; then at the end of its life, recycle that product to squeeze maximum life and profit out of it,” Meyer explains.

Best Practices Revealed

How can companies get started on the path to implementing green reverse logistics processes that yield a healthier bottom line? Here are a few best practices to follow, from companies and experts who practice what they preach.

Understand Your Product From Beginning to End

The first step is to truly understand the product’s impact, from the start of the manufacturing process until the end of its useful life. Although reverse logistics concerns only the reverse half of the supply chain, the implications for its success begin with the forward supply chain.

“Companies need to understand what resources are used in their manufacturing process; whether any of those products are hazardous; which components can and cannot be recovered and reused. Then they need to examine the various waste streams and outputs associated with the process,” Meyer explains.

This approach means thinking of reverse logistics at the beginning of a product’s lifecycle, and designing with its end-of-life disposition in mind. “Don’t take an end-of-the-pipeline solution; start instead with the initial product conceptualization and design,” Meyer advises. “Designing a product in a way that reduces the amount of hazardous materials that are used and maximizes the use of those materials so they can have an extended life, will reduce the product’s overall long-term environmental impact.”

This “designing with the environment in mind” aspect of reverse logistics is key for global telecom supplier Ericsson. The company tweaked its designs to reduce operating energy consumption; reduce product weight and volume; remove banned or restricted substances; and keep product disposal in mind throughout its product development process. The philosophy has helped Ericsson decrease the raw material footprint of its mobile switching center products by 70 times over the past 10 years.

This approach is also key to boosting profitability, because a product design that uses fewer resources and allows for easy reuse or recycling at end of life generally translates into lower overall production costs. Meyer cites the example of a solar panel manufacturer in Portland, Ore. The firm contracted with a local recycling company that collects and reclaims some of the waste, including slurry filter cake and graphite, produced in the manufacture of solar panels. The recycler is able to turn some of that waste into a material that the solar panel manufacturer can reintroduce into its production process.

Be Creative About Finding Value

When products are returned to a manufacturer (or to a third party that handles reverse logistics for the manufacturer) several scenarios usually arise:

- The product is still functional and can be repackaged— or repaired/remanufactured if necessary— and sold as refurbished goods in a secondary market.

- The product no longer functions but can be harvested for parts that still have value.

- The product has reached the end of its life and must be disposed of in some way. At each of these points, companies can be creative about how to find value in the product, while still adhering to green practices.

“One of the greenest parts of reverse logistics is that it turns material that used to end up in the landfill into something useful,” says Liz Walker, vice president of marketing and business development for Image Microsystems Inc., an Austin, Texas-based company that provides repair, refurbishment, and reverse logistics services. At the company’s depot, for example, it tries to find a value or a use for everything that comes through its doors. This is where it helps to be creative.

Take e-waste plastics— such as the plastic in spent printer cartridges or on cell phone housings. They are a major environmental issue for today’s electronics manufacturers because the goods usually “have no value in the downstream recycling supply chain and are burdensome to dispose of,” Walker says.

To combat this issue and find additional value for its clients, Image Microsystems has developed a process where it grinds and compresses e-waste material into an earth-friendly material that it uses for sign substrate. “We work with a major computer OEM in Austin that uses these signs— made from its own e-waste— on its corporate campus. It’s a unique closed loop,” she adds.

Don’t Forget About Transportation

While much of green reverse logistics focuses on returned goods and how best to reuse or dispose of them in a cost-effective and environmentally friendly way, the reverse logistics process also has a variety of transportation and carbon footprint implications. Greening returned goods processes but ignoring reverse transportation concerns makes for an incomplete green reverse logistics strategy.

“The procedures required to ensure timely processing and turnaround of returns directly affect transportation,” write supply chain consultants Wayne Burgess and Craig Stevens in a recent whitepaper, Reducing the Environmental Impact of Returns. The authors advocate a centralized returns process in order to decrease multiple shipments and location transfers.

“Shipping consolidated lots holds clear carbon footprint gains, which are closely matched by a decrease in fuel costs,” they say.

That was certainly the case for a large office supply retailer that partnered with Image Microsystems to gain reverse logistics efficiencies. The company, which sells computers, printers, and other consumer electronics, now ships all its returned products to Image Microsystems’ facility, regardless of whether the products are to be repaired, resold, or scrapped.

“We developed software to help the retailer analyze— right at the point of return— what needs to be done with that product, so it does not have to ship products to different facilities around the country depending on the work required,” Walker explains.

If a product has to be scrapped, Image Microsystems handles that process; if the product can be resold, the company becomes a virtual store for the retailer, fulfilling orders out of the refurbished inventory it holds for the retailer. “This takes several legs out of the reverse journey, and prevents the retailer from incurring extra carbon footprint and transportation costs,” Walker notes.

Ultimately, whether it is the actual products being returned, or the process by which a company returns them, reverse logistics can— and should be— both green and cost-effective. “The benefit to green reverse logistics is tangible,” says RLA’s Jeff Robe. “Most companies are realizing that being green means being more profitable, too.”

Adding Up Green Gains

It’s one thing to talk about the benefits of sustainability initiatives, but the proof is in the spreadsheets. Let’s crunch the numbers on three companies’ reverse logistics results.

Cisco

Strategy: Partnered with third-party provider to revamp reverse logistics processes.

Payoff: Transformed an $8-million cost center into a $147-million profit source.

Palm Inc.

Strategy: Focused on refurbished goods for resale in secondary channels.

Payoff: Cut processing costs by 50 percent; reduced returned goods inventory to less than two weeks; tripled product recovery rate; receives up to 80 percent of retail selling price for returned goods.

Ericsso

Strategy: Redesigned products to reduce operating energy consumption. Reduced product weight and volume, removed banned or restricted substances, and planned for product disposal.

Payoff: Decreased product raw materials footprint by 70 times over the past 10 years.

Case Study: Philips Consumer Lifestyle

Sustainability+Profitability=Total Reverse Logistics Efficiency

Consumers who purchase a Sonicare toothbrush, decide after a few uses that it’s not for them, and return it, probably never think about what happens to that product after they receive their refund. But for Philips Consumer Lifestyle— maker of Sonicare, Norelco shavers, Avent baby products, and a variety of consumer electronics goods— what happens to returned products is crucial to the bottom line and to its sustainability goals.

Because of the nature of their use, returned products such as toothbrushes, shavers, and baby bottles cannot be resold and must be disposed of. But just heaping them in a garbage dump does not meet Philips’ zero-landfill goal. To make sure its products do not end up in landfills, Philips works with third-party logistics provider Ryder Supply Chain Solutions to select partners that can provide proper disposition.

“Our zero-landfill goal is critical when selecting partners,” notes Tony Sciarrotta, senior sales manager for Philips Consumer Lifestyle. “We don’t want a partner to put our products in a dumpster.”

Sciarrotta’s division also has stringent environmental guidelines for handling returns of its consumer electronics goods. Together with Ryder, it has crafted a reverse logistics process that helps it refurbish, reuse, and resell nearly 80 percent of these returned goods.

Because most of the finished goods returned to Philips Consumer Lifestyle still function well, the key emphasis is on repackaging and reselling these products as refurbished goods— and doing so in a cost-effective and green manner. Returned products are shipped to a 500,000-square-foot facility in Groveport, Ohio, which Ryder operates for Philips Consumer Lifestyle.

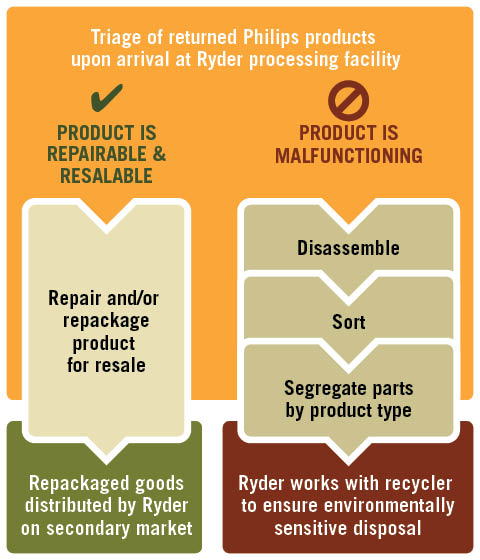

There, Ryder runs a triage operation to determine if goods are resalable or malfunctioning, and whether it makes business sense to repair them for resale, or dispose of them (see chart). If they are to be resold in a secondary market, Ryder manages the distribution of those repackaged goods. If they can’t be resold, Ryder disassembles, sorts, and segregates parts by product type and works with the recycler to ensure they are disposed of in an environmentally sensitive way.

Most of Philips Consumer Lifestyle’s returned goods still function well, so the company relies on third-party logistics provider Ryder Supply Chain Solutions to handle returns correctly. To ensure consistency, a technology solution guided by business rules determines how to direct the returned product through each step in the reverse logistics process. Here’s how it works.

“Our goal is to determine the greatest value Philips Consumer Lifestyle can get from its returned assets, and execute in a green-friendly fashion— as quickly and cost-effectively as possible,” says Chad Burke, director, supply chain excellence for Ryder. To that end, Ryder developed an IT solution with business rules that govern when goods should be set up for resale or put through the disposition process. “We make a business decision on returned products based on their cost and retail sale price point,” Sciarrotta explains. “A product that sells for less than $100 at retail, for example, is not worth refurbishing.”

The IT solution has increased the velocity of reverse logistics for Philips Consumer Lifestyle, and brought much-needed transparency to the process. “The system gives Philips immediate visibility to what is being returned, when credits have been initiated, and what path those products will take, as well as a feel for the amount of refurbished inventory it has on hand,” Burke explains. “This visibility to the whole process helps the company make better decisions and lessens its impact on the environment.”

Ryder also handles reverse transportation for Philips Consumer Lifestyle, consolidating product returned from retailers to “reduce the number of trips, and the associated carbon footprint and costs,” notes Norm Brouillette, Ryder’s group director, supply chain solutions. Having Ryder handle both the reverse logistics processes and forward distribution of repackaged goods out of its Grovepoint facility allowed Philips Consumer Lifestyle to cut its transport costs and fuel use, and leverage its building’s carbon footprint.

“Rather than have a separate third party handle distribution and incurring duplicate transportation and carbon footprint costs, we do everything in one facility and cut down on the need for multiple shipments,” Brouillette explains.

As an additional green benefit, Ryder uses recycled cardboard and paper rather than petroleum-based products when it repackages and ships returned goods to secondary sales channels. “At our request, they try not to put anything into the waste stream that has a negative effect on the environment,” Sciarrotta says.

“We view reverse logistics as the ultimate recycling process,” he adds.

Reverse Resources

For additional information on green reverse logistics, consult the following reports and whitepapers.

Maximizing Recovery While Minimizing the Environmental Impacts for Reverse Logistics

By Paul Rupnow, Reverse Logistics Association

Reverse logistics industry leaders offer strategies, tactics, and insights to maximizing recovery while minimizing environmental impact.

Green Logistics: Sustainable 3PL Practices for Reverse Logistics and Asset Management

By GENCO ATC

This resource explains the green benefits of reverse logistics and offers tips on determining when to refurbish products and selecting a 3PL for reverse logistics and asset management.

Reducing the Environmental Impact of Returns

By Wayne Burgess and Craig Stevens, partners, ReturnTrax

This whitepaper examines the areas of environmental concern regarding returned goods, and proposes mechanisms and programs to minimize the impact.