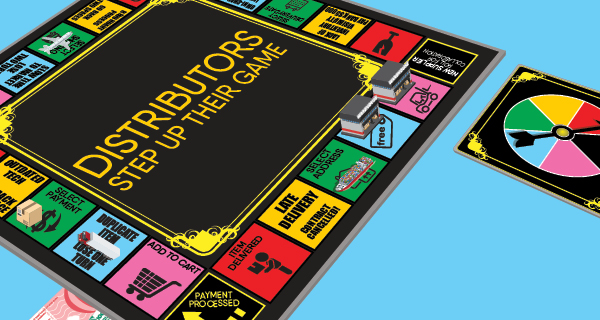

Distributors Step Up Their Game

Changing business models—especially the rise of e-commerce—are prompting many distributors to enhance their services. Game on.

4 Ways Distributors Can Stay Competitive

It might seem that the rise of e-commerce, which allows customers and manufacturers to more easily interact directly, would leave distributors with no role to play. To be sure, online transactions appear to be having an impact on the distribution sector. Estimated sales of U.S. merchant wholesalers between 2014 and 2015 dropped from $7.7 billion to $7.3 billion, according to the U.S. Census. The decline may be a result of more consumers and large retailers transacting directly with manufacturers, says Arnold Maltz, associate professor, supply chain management, at Arizona State University.

Yet it’s too early to count distributors out. They play a key role in helping companies more efficiently access both suppliers and customers. Moreover, many are enhancing the services they provide.

Distributors typically are critical to industries with numerous, relatively small providers, or where end buyers need to purchase small amounts of products from a range of suppliers. “If the industry has lots of products and customers, distributors can aggregate demand,” Maltz says. “You get economies of scale.” Distributors also can be essential when companies enter new markets, particularly overseas or in rural areas, he adds.

Distributors also can assist companies that make regular, repeat purchases of products to keep their factories running, says Mark Dancer, president of Channelvation, a provider of channel strategies and solutions, and a fellow with the NAW Institute for Distribution Excellence. Some distributors stock repair parts for machinery and/or provide custom logistics solutions.

They’re also “problem solvers,” Dancer says. Good distributors know their customers’ operations, and can help them choose products to keep those operations humming.

One example is Electri-Cord Manufacturing Co., based in Westfield, Pennsylvania, which provides wiring harnesses, cable assemblies, power cords, and other products to the military, medical, telecommunications, and other industries. Many customers require quick turnaround of complex assemblies.

Electri-Cord works closely with six distributors, including through vendor-managed inventory (VMI) programs, to maintain rapid access to materials at its U.S. and Mexico plants without having to purchase them upfront. It works with several dozen other distributors less frequently.

“Distributors account for approximately 80 percent of everything we buy,” says Jason Samuels, director of materials for Electri-Cord. The company regularly needs, for instance, 10 custom units at reasonable prices and with short lead times. It’s often not feasible to stock up or work directly with manufacturers, “when we need to build something today, but didn’t know about it yesterday,” he says. “That’s where distributors come in.”

Electri-Cord works with distributors in a range of ways. It may execute stocking agreements and share forecasts of material needs to ensure distributors’ pipelines remain full.

It tends to use VMI programs for components that turn rapidly. With a VMI, the parts are physically onsite at an Electri-Cord location, yet the company doesn’t own or pay for them until they’re pulled from the vendor’s inventory. “This helps us increase availability, decrease lead times, reduce risk, and keep dollars in our pocket,” Samuels says.

Under Good Authority

Electri-Cord makes a point of working with authorized distributors. Distributors that aren’t authorized by the manufacturers may carry the parts Electri-Cord needs, but typically won’t offer after-sales support. “We want traceability, visibility, and support,” Samuels says, adding that Electri-Cord employees often talk with their distributors multiple times each day. “Our distributors help us modify or expedite orders, or get answers about quality. They’re truly our partners.”

Transparency is key in any distributor relationship. “You should be able to tell if the distributors’ pricing is fair, and what they’re charging you for,” Maltz says.

On the Sales Side

Just as important as the expertise they offer on the supply side, distributors also can facilitate manufacturers’ efforts to reach customers. Many bring a strong understanding of local and niche markets. “While manufacturers might see the big picture, distributors are good at optimizing the products on the shelf to meet local market needs,” says Dancer.

Eaton, the $19.7-billion power management company, collaborates with its distributors as “an integral part of our go-to market strategy,” says Marielle Cage Couvat, logistics solution and program manager. “Distributors bring strong market presence, a wide product assortment, flexibility and logistics capabilities, a warehousing footprint, multiple stocking locations, and smaller size orders.”

Distributors can apply customer feedback to help Eaton define the needs of its markets. For instance, many distributors have assembled specialized “energy sales teams” to provide customers with information on the estimated payback of Eaton’s LED and lighting control products. This can be an important element of the sales process.

“They audit the customers’ energy spend on old technology and use Eaton’s calculators to show our collective customers paybacks in energy and maintenance savings, as well as greenhouse gas emission reductions,” Couvat says.

Another way distributors can help boost sales is by including a manufacturer’s products within a package of complementary products. ACR Electronics Inc., Fort Lauderdale, Florida, develops emergency beacons for the marine, aviation and other markets. Many of its distributors carry a range of safety products, such as life jackets and life rafts, from multiple companies. “Our products are best sold with a whole safety package,” says spokesperson Nichole Kalil.

The Import Channel

Smaller businesses that import goods often find it practical to work through distributors. Ceramic Tile Design (CTD) imports tile from Italy, Spain, and several other countries. It has three divisions: one for the residential and light commercial market, one focused on large commercial projects, and a distribution division.

When the company started importing tiles, Steve Cerami, president and chief executive officer, decided to act as a distributor to help turn the inventory CTD would gain. “We created a channel to market the imports,” he explains. “It gives us best pricing and territorial protection.” That allows the firm to more effectively compete for many commercial projects.

Moreover, CTD sells to many showrooms that aren’t set up to import tiles. They’d have to inventory the product, buy in volume, and establish relationships with the factories. They’d also need to hire support staff and salespeople, and implement computer systems to handle the distribution operation. “Our infrastructure is formidable,” Cerami says.

While distributors continue to offer value, the growing tendency of both consumers and businesses to transact directly with manufacturers is changing their business models. “They’re offering more services and solutions,” Maltz says.

“Distributors don’t control markets,” says Wade McDaniel, vice president of solutions architecture for Avnet, a $26-billion Phoenix-based distributor of electronic components and embedded solutions. “As customers and suppliers change, we have to change.”

For instance, more customers are looking for “end-to-end solutions,” McDaniel says. “Our customers want to engage us at the beginning design stage and take it through to volume production.”

Avnet’s 2016 acquisition of Premier Farnell is helping them do this. “By pairing our deep expertise in large volume, broadline distribution with Premier Farnell’s specialization in proof of concept and design, we can offer true end-to-end solutions that accelerate a customer’s time-to-market and moves their products seamlessly from prototype through volume production,” according to a statement by William Amelio, Avnet’s chief executive officer.

More Than an Order Taker

The ease with which customers can find information online also is impacting distributors’ operations. Both business and consumer customers increasingly search the web for answers to questions—say, the parts needed to fix a pump—they previously would have posed to their distributors. To compete, distributors have to provide even deeper levels of expertise. “They can’t just meet orders,” Dancer says.

Among other actions, top distributors are investing heavily in employee training and outfitting many workers with tablets and other tools so they can offer in-depth product and logistics advice, no matter where they are. Some distributors offer product training programs for their customers’ salespeople.

A growing number of distributors are implementing online portals and other tools that allow customers to easily track purchases, including information such as the prices they paid and the percent of on-time deliveries. “The best distributors work with the analytics to help customers improve their products and processes,” Dancer says.

Distributors increasingly need a full complement of strong supply chain processes. This includes inventory management and planning, effective transportation services, and an extensive warehousing footprint that crosses multiple geographies. They also need to accommodate spikes in demand, and have a diverse product portfolio and strong multi-channel presence.

Top distributors also will track and report the services they’re providing. “If the distributor is selling for you, they’re between you and your customer,” Maltz says. “You don’t want to lose that connection.”

A growing number of distributors are adding services that fall outside a pure distribution model. One example: a roofing distributor that also installs roofs becomes a one-stop shop,” Dancer says.

To be sure, this can bring distributors into competition with their customers, in what’s sometimes referred to as co-optition. For example, some of Electri-Cord’s distributors have added manufacturing capabilities. In some cases, the two companies work together, and in others, they compete. Samuels notes that distributors are in direct contact with many customers. That gives them a constant flow of information on customers’ challenges, plans, and preferences. “We’ll watch this closely,” he says.

Some distributors are developing “digital twins,” which are digital representations of their physical operations, such as the trucks on the road or the products being built. “This is where distribution services are headed,” McDaniel says.

The reason? Having this information allows distributors to more quickly make decisions and respond to customers.

That’s critical, given the pace at which their businesses, and those of their customers, are changing.

4 Ways Distributors Can Stay Competitive

Asset-light e-marketplaces and other non-traditional shopping channels, combined with shifting demographics, are rapidly upending industrial distributors’ inventory-heavy model. As a result, distributors must quickly adapt and address threats with everything from sharper mobile offerings to upgraded customer service, a new whitepaper from UPS shows.

According to the UPS Industrial Buying Dynamics Study: Buyers Raise the Bar for Suppliers, the biggest shift comes from millennials (defined for this study as those currently ages 21-34) who grew up in a digital era and are bringing their tech-savvy and nontraditional purchasing habits—for example, bypassing the middle man and working directly with the manufacturer—with them into the workplace. The impact on the future of industrial products purchasing may be among the most profound of any modern generation of buyers and provide a glimpse of the future.

The report surveys 1,500 buyers of industrial products who are between the ages of 21 and 70 in the United States. It captures a sector undergoing demand changes and channel shifts at a startling speed: 81 percent of buyers have purchased directly from manufacturers, up from 64 percent in 2015. Meanwhile, 75 percent of buyers surveyed have shopped at an e-marketplace, soaring from just 20 percent in 2013. What’s more, 80 percent of buyers are likely to shift to suppliers with a more user-friendly web presence, up from 72 percent two years ago.

“With e-commerce, industrial buyers can choose from numerous suppliers with the click of a button, leaving the traditional business-to-business distributor model threatened,” says Matthew Guffey, vice president of UPS segment marketing. “Maintaining the status quo, even just for now, is not an effective solution. Distributors have to up their game.”

The paper identifies four main ways for distributors—including those with smaller ambitions or limited funds—to remain competitive and offers solutions to reach young corporate buyers where and how they want to interact:

- Recognize rising threats. It is imperative to consider strategic investments that bring services to parity with competitors. The paper finds that more than half of respondents working primarily with distributors intend to increase e-marketplace spending, representing a looming risk to distributors.

- Think digital. Online channels are a necessity and distributors need to strengthen e-commerce capabilities, particularly for mobile ordering. Thirty percent of corporate buyers use mobile channels to order industrial products, and 24 percent are “extremely likely” to do so in the future. Nearly half of all buyers—and 69 percent of millennials—indicate they would likely shift business to a distributor offering a mobile app.

- Address buyers’ needs by product. Partnerships can help make businesses more competitive. Look into purchasing insurance on products and shipments to mitigate risk and to help protect and improve cash flow; leverage a logistics provider’s global network to ramp up service more quickly and reach more pockets of growth.

- Go beyond the sale. Buyers want interaction beyond the sale (i.e. post-sales support), with half of respondents stating they would switch to a supplier offering assistance with returns, training, and on-site maintenance or repairs. Thirty-six percent of millennials need services at least once monthly, compared with just 8 percent of Baby Boomers, according to the study.