Keeping Intermodal In Your Sites

Eyeing a new location for your plant or DC? Make sure it’s rail/intermodal accessible, and served by progressive transportation providers.

Intermodal Matters

What’s Developing at Watson

Rail is resurging. After more than one decade during which a combination of sea, air, and over-the-road addressed most shippers’ transport needs, a myriad of forces is bringing domestic intermodal rail back into the picture.

Acknowledging the challenges confronting motor freight carriers—from driver shortages, Hours-of-Service regulations, and electronic log book requirements to rising fuel costs and declining road infrastructure—railroads have been improving track and facilities, as well as service offerings, to meet the needs of a wider array of shippers. The level of coordination among modes is also on the rise, as trucking companies use rail for some legs, and vice versa.

At the same time, shippers are shifting their approach to manufacturing by moving final assembly processes closer to market. As they reconsider their networks, shippers are viewing rail as an opportunity to bypass busier ports, speed shipments, and find new ways to get to customers.

Changing transportation patterns have driven an increase in domestic intermodal. Total intermodal shipments grew 4.6 percent in North America in 2013, and domestic container volume was up 9.4 percent, according to the Intermodal Association of North America. While rail intermodal’s percent of volume can still be measured in the low single digits compared with trucking, it is growing at a healthy clip.

The New Rail

Rail has resurged in the past. But this time, it’s different. “In the heyday of the 1990s, railroads worked with shippers by presenting rail-served facilities or by bringing in a spur,” recalls Bill Luttrell, senior locations strategist for transportation and logistics provider Werner Enterprises. “Today, the mindset has changed. Railroads are more interested in keeping the main line going, therefore manufacturing and warehouse/distribution center site selection is more focused on existing and planned intermodal facilities.”

Domestic intermodal is taking its place beside international transportation as a key component of supply chain management, particularly for consumer products and finished goods.

“International distribution was the key driver of the intermodal craze in the early 2000s, followed by domestic movement and the conversion of truck to rail in the past three to five years,” says Michael Murphy, chief development officer for logistics-focused developer CenterPoint Properties. “Now, the signs point to manufacturing coming back. Companies considering a new plant are looking at labor and logistics/transportation benefits.” CenterPoint’s pipeline is starting to see increases in the number of manufacturers wanting new facilities near roads and intermodal.

It makes sense to consider rail and intermodal, especially when moving cargo more than 500 miles. “Companies are starting to locate along major intermodal corridors, and taking a closer look at intermodal facilities,” says Luttrell. But others report profitable use of domestic intermodal at even shorter distances.

THE FEC ADVANTAGE

It’s hard to find a more clear-cut alternative to trucks than Florida East Coast Railway (FEC), which stretches 351 miles from Jacksonville to Miami. Like a truck carrier, the railroad provides scheduled service: six trains daily in each direction, so it can offer late cut-off times. FEC uses concrete rail ties that enable autos and carloads to mix with intermodal containers on each train. This infrastructure allows the train to maintain the speed needed to meet shippers’ tight delivery schedules.

Increasing demand for intermodal at a congested Ft. Lauderdale facility prompted FEC to initiate a $73-million, 42.5-acre intermodal terminal at Port Everglades. The facility will increase FEC’s intermodal capacity from 100,000 to more than 450,000 lifts daily. The facility, scheduled to open in July 2014, will use wide-span cranes to transfer both international and domestic containers between ship and rail. It will also handle domestic containers originating in, or destined for, U.S. markets on the East Coast.

The service offers numerous advantages. “Many ocean carriers don’t want their international containers moving inland because it’s expensive to truck them back to the port,” explains Jim Hertwig, president and CEO of Florida East Coast Railway. “But, because FEC has many 53-foot domestic containers, we can transload cargo from three 40-foot containers to two 53-foot containers, which can be in Atlanta or Charlotte in two days. And it’s all backhaul traffic, so shippers derive that economic value.”

FEC also offers on-dock rail at the Port of Miami, one of only three East Coast ports that will accommodate larger steamships using the widened Panama Canal, with four Super Post-Panamax 65-long-ton cranes and a deeper harbor. In addition, by enabling an all-water route from west to east to reduce fuel costs, Port Miami will serve as a transshipment hub when shipments arriving from Asia are dropped there, then quickly transloaded.

The economic benefits of using rail through Florida are clear, but shippers can also reduce transportation costs by taking advantage of the large parcels of rail-adjacent property FEC owns on Florida’s east coast. The region also offers a strong workforce and an expanding population.

“Some shippers say you can’t use intermodal for freight moving fewer than 500 miles, but 45 percent of FEC’s business is 350 miles or less,” says Hertwig. “We do it every day.”

Front and Center

Railroads such as FEC, as well as real estate developers and business development groups, are eager to help shippers find ideal locations to meet their emerging needs among the many existing, new, and planned intermodal facilities cropping up—particularly in the center corridor of the United States.

Much of the investment in new or improved rail intermodal facilities is taking place in the center of the United States—near the interstate highway system, but far from already congested port locations. Shippers are tapping into this central location in a variety of ways—to not only serve local markets, but also to reach a substantial portion of the U.S. population within a one-day drive.

Intermodal facilities bring together two or more modes—often rail and truck carriers, but sometimes barge as well. Some shippers appreciate the opportunity to use a single provider for both the rail and trucking portions of their transportation by engaging intermodal services.

In some cases, containers arriving at East or West Coast ports move directly onto rails bound for central U.S. ports, where they are unsealed and processed through Customs. Another option is moving cargo via barges traveling up the Mississippi to ports along the waterway, then by rail to intermodal facilities.

Locating distribution centers in the immediate vicinity of intermodal facilities enables shippers to reduce drayage costs, because sites are often available in close proximity. “We find the drayage maximum is 200 miles,” says Luttrell. “A good intermodal facility will serve a lot of people within 200 miles.”

Shippers maintaining facilities within intermodal parks report drayage costs as low as $35 per haul, versus $150 to $200 for longer hauls.

For example, CenterPoint Properties completed inbound international container distribution centers near intermodal facilities for two major retailers: Walmart, adjacent to BNSF’s facility at CenterPoint Intermodal Center in Elwood, Ill., and Home Depot, near Union Pacific’s Joliet, Ill., facility. The retailers bring in containers from Asia, expedite them through West Coast ports, and load shipments onto trains for the five-day trip to these facilities, which are also foreign trade zones.

Once containers are transferred onto chassis, the retailers’ own employees transport them the short distance to their facilities, where containers are opened and goods are distributed to stores, eliminating lengthy drayage moves by third parties.

“Walmart and Home Depot control the timing, eliminate cost in their supply chain, and ultimately handle product efficiency and create revenue on a timely basis,” says CenterPoint’s Murphy. Home Depot’s drayage savings alone paid for its annual rent on the facility, he adds.

In newer or expanded intermodal facilities, sites are often available near loading and unloading operations, which shortens drayage distances. Inland intermodal facilities often encompass an entire 360-degree area in which to offer sites, compared with the half-circles around seaports. Land rates are usually lower for intermodal ports located away from major metropolitan areas.

While large retail and consumer goods companies are driving much of the increase in domestic intermodal, automotive and a few other industries are also increasing their use.

Once companies empty their inbound containers, they often then use them to move raw materials such as grain and corn, or even partially assembled products outbound. Some shippers derive cost benefits from using their containers for backhaul, and steamships get their containers back faster, which generates more revenue. Other uses for inbound containers include sub-assemblies moving back to international locations.

The Right sites

The U.S. central corridor offers a number of current and pending intermodal centers with sites available for manufacturing and distribution facilities. Here are a few options:

Canadian National’s RidgePort Logistics Center, Memphis, Tenn., offers access to rail, truck, and barge services, as well as to Canadian National Railway’s (CN) complete network, enabling shippers to reach three coasts seamlessly. The new logistics center will have 800 acres of land for development, with the first availability by fall 2014.

That access only makes Memphis more attractive to manufacturers and distributors looking to site new facilities, says Sean Goff, director of planning and development for CN’s Intermodal Group.

“Because CN offers single-line service, and leverages the geographic advantages of Prince Rupert and Vancouver, it is able to provide shippers a speed advantage,” says Goff. “We can operate an 18- to 20-day service from Shanghai to Memphis, dependent on port rotations.”

Taking advantage of the Memphis area’s central location, strong highway capacity, and intermodal capabilities are major companies including Disney, Cummins, Toyota, Nike, and Brother International Corporation. Government and business development resources offer a full complement of assistance services and incentives to help new companies locate in the area.

RidgePort’s location, combined with its array of services, “allows ocean shippers to consolidate operations in a single terminal and railway, and cut logistics and drayage costs,” says Goff. One such service is matchback—where CN’s Supply Chain Logistics Group works with the steamship lines to facilitate loading of containers back to the port of origin—for example, transloading containers with grain back to Asia, reducing costs for all parties.

With its full-service forwarding unit, CN’s Supply Chain Logistics Group can also manage cargo all the way from origin through destination, so shippers deal with only one service provider for the entire move.

The CN RidgePort Logistics Center was developed by Jones Lang LaSalle and Ridge Property Trust to meet CN’s unique market requirements.

CenterPoint Intermodal Center (CIC), Joliet and Elwood, Ill. Located 40 miles southwest of Chicago, CenterPoint calls its Intermodal Center the largest master-planned inland port in North America. The CIC, which encompasses both the Union Pacific and BNSF intermodal terminals, covers more than 6,500 acres and is adjacent to the I-55/I-80 interchange. CenterPoint also manages a barge terminal in Joliet.

Besides price competitiveness, the proximity of the two intermodal facilities offers a unique benefit to shippers: two independent supply chains coming together in one location. “That’s a rarity,” says Murphy.

CenterPoint Intermodal Center still has many available sites near each intermodal facility. In addition to the low drayage costs, other benefits include a foreign trade zone designation; the presence of new road, water, and utility systems; and skilled labor in the area.

“Shippers bringing 2,500 containers or more into the Chicagoland area should consider whether to locate a warehouse closer to intermodal facilities to gain economies of scale,” advises Murphy.

Heartland Intermodal Gateway Facility, Wayne County, W.Va. The Wayne County Economic Development Authority is on a mission to make the West Virginia region a national transportation hub. A $30-million intermodal facility— which occupies about 100 acres adjacent to Norfolk Southern’s terminal and is expected to open in Prichard, W.Va., in July 2015—is helping that effort considerably. With a full array of rail, air, highway, and waterway assets, the region is well prepared to take on the role, says Brandon Dennison, associate director, Wayne County Economic Development Authority.

Shippers in the region will also benefit from Norfolk Southern’s $50-million investment in its Heartland Corridor, which raised tunnels to accommodate double-stacked railcars. Several major shippers have selected nearby locations to site their distribution centers, and the Authority is working on a foreign trade zone designation.

“This area offers huge potential for warehousing around the intermodal facility,” says Dennison. “Wayne County has been a well-kept secret, until now. Logistics managers are pleasantly surprised when they find out what the area offers.”

Its central location, which reaches more than half the U.S. population within a one-day drive, is just one reason shippers are looking at Wayne County. “On-demand, on-time delivery is what shippers are all about, and we’re located in the ideal place to take advantage of that,” Dennison says.

A favorable, low-cost business environment is also a big draw. West Virginia’s cost of living is 3.2 percent lower than the national average. And taxes are down: The state’s corporate net income tax rate was reduced from 8.5 percent to 7.6 percent in recent years, and its already reduced business franchise tax will be eliminated by 2015. The state also offers a package of incentives for businesses relocating to the area.

Wayne County ensures a strong supply of skilled workers through Mountwest Community and Technical College, and the Robert C. Byrd Institute for Advanced Flexible Manufacturing, complemented by Marshall University’s School of Business. Employee turnover is below the national average at 8.5 percent, and West Virginia, at 4.5 percent, is tied with New Hampshire for the third-lowest turnover rate among manufacturing industries.

“The Heartland-Gateway project provides extraordinary potential forimproving efficiencies and reducing costs across the warehousing and distribution landscape of the Mid-Atlantic and central Appalachia,” says Don Perdue, executive director of the Wayne County Economic Development Authority.

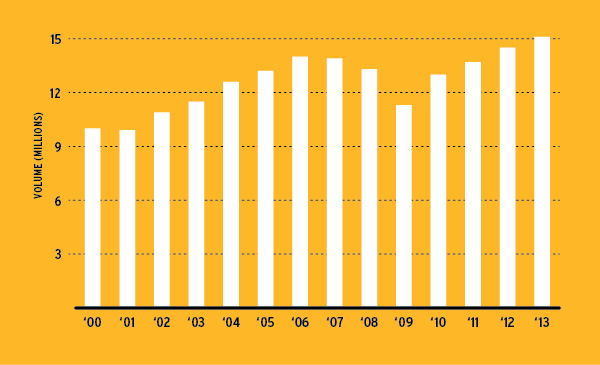

Total Intermodal Loadings 2000-2013

As intermodal volume continues to grow, access and proximity to intermodal and rail facilities play an important role in site selection.

Source: IANA Intermodal Market Trends & Statistics Report

Shovel-ready Shelby

When shippers settle on an ideal site for a new manufacturing or distribution facility to service their supply chain and their customers, they want to get it up and running quickly. Shelby County, Ind., just southeast of Indianapolis, is working to satisfy that need with two state-certified, shovel-ready industrial sites—an indication that the utilities are installed and ready for construction to commence. An independent site consultant is also engaged in certifying the sites so that they will, in turn, also be certified by CSX.

CSX has a spur from Indianapolis to Shelbyville, Ind., and a short line operates between there and Cincinnati. These railways support a number of local, foreign-owned automotive suppliers for whom rail is a priority, such as the Honda assembly plant less than 20 miles away in Greensburg.

“Shippers are overlooking a lot of opportunity in Indiana, especially in the central and southern parts of the state,” notes Harold Gutzwiller, manager, economic development and key accounts at Hoosier Energy, which provides power to the sites, and offers advice and incentives for energy efficiency. “These could be great distribution center sites, because they’re near and accessible to rail.”

Shelbyville is hoping to convince CSX to build a full intermodal facility in the area to support its growing industrial base. An intermodal facility could help local companies by enabling them to bring in more cargo via rail, as well as cargo traveling via barge to Cincinnati, then via rail to Shelby County.

A proposed intermodal facility would complement several other investments. The City of Shelbyville is constructing a new road connecting one current and two proposed industrial parks to Interstate 74, which parallels the CSX line. The city is also considering expanding its small local airport.

In addition to Shelby County’s central location, other attractive features include a low cost of doing business, a ready workforce, and a business-friendly regulatory system and low-tax environment. Shelby County Development Corporation is partnering with a local junior college and local utilities to train workers for industrial jobs.

Packages of tax credits and training funds are also available. “Our city and county collaborate successfully, and that’s not something you see often,” says Dan Theobald, executive director of the Shelby County Development Corporation.

SHOW ME Neosho

Some shippers say the United States has a second four corners, where Missouri, Oklahoma, Kansas, and Arkansas come together. That easy access to four states—as well as 70 million people within a one-day drive—is what has attracted shippers in consumer goods, pet nutrition, and custom machining to the Joplin and Neosho, Mo., region.

That popularity only promises to grow as the region develops an intermodal facility, expected to be complete within two years.

The area is already served by two Class I railways—Kansas City Southern and BNSF—as well as five major north-south and east-west highways, including I-49 and I-44. Two major inland waterways also intersect in Missouri, creating a confluence of modes in a central U.S. location.

About 50 trucking companies operate headquarters or major operations in the area, supported by two colleges with robust driver training programs. Those programs, combined with double-digit population growth, ensure a continuous flow of new drivers. Population growth and a preponderance of warehouses also guarantee a ready supply of workers to staff manufacturing and distribution facilities.

Currently, companies such as Jarden Consumer Solutions and Missouri Walnut are moving a high volume of inbound and outbound intermodal containers from the area. New sources of such freight also are on the horizon.

Upcoming Upgrades

That volume promises to increase as the 500-acre Neosho Industrial Park introduces important upgrades. Business groups are working closely with railroads to create a service offering with strong appeal for intermodal shippers. The park will soon contain a 275-acre Foreign Trade Zone, a convenience for shippers who are also drawn to the area’s low cost of doing business. The state enhances that competitiveness through Missouri Works, a package of incentives based on job creation and capital investment.

The Neosho/Joplin area’s amenities, together with its central location, create an ideal environment for intermodal shippers. “It’s great to have access,” says Mike Franks, executive director for economic development for the Neosho Area Business and Industrial Foundation Inc. “But better yet, we have a low-cost point of access.”

Shippers locating sites near rail intermodal facilities can optimize their use of all modes to create an effective and efficient supply chain network.

Intermodal Matters

There are a number of factors to take into account when selecting a manufacturing or distribution site near an intermodal facility.

The basic steps for choosing an industrial site include a logistics lane and centroid analysis; site screening and selection; site visits; and negotiations, according to Bill Luttrell, senior locations strategist for transportation and logistics provider Werner Enterprises. If one goal is to increase intermodal use, that analysis should consider intermodal facility availability early in the process.

Lane and centroid analysis uses software to identify regions that satisfy needs, such as proximity to suppliers or customers. A pro forma analysis looks at a shipper’s needs over the next three to five years. If rail access is a criteria, for example, the analysis looks for facilities within approximately 300 miles of identified regions.

Additional site selection considerations include:

- Access to major truck corridors.

- Workforce availability and readiness. Some verticals require access to seasonal workers to accommodate surges. Competition for labor is also a factor. Some locations also stress the availability and training of truck drivers.

- Intermodal facility location and characteristics. Intermodal facilities that have invested in state-of-the-art cranes can load and unload more efficiently, speeding cargo transfers. Some offer specialized capabilities, such as handling trailer on flatcar, or reefers.

- Proximity to customers and/or suppliers.

- Site characteristics, including the cost of land, and the availability and readiness of utilities.

- Incentives. Many state and local governments have prepared packages of tax advantages to attract shippers.

- Availability of a foreign trade zone, if applicable.

- Livability. The cost and quality of life for workers.

In site visits, shippers typically meet with officials and interview shippers already operating in the area. Some companies engage a site selection consultant to steer them through the process.

Although Werner is a trucker at heart, “we are one of the few large transportation and logistics companies offering site selection services,” says Luttrell. “Location is an integral piece of the supply chain puzzle, so we build our site selection process heavily around logistics and supply chain factors.”

Luttrell is responsible for advising clients on where to build manufacturing and distribution sites, as well as for the carrier’s own site selection process. That includes locating in intermodal facilities.

Werner embraces appropriate use of rail. “We look at intermodal as yet another way to move goods on behalf of shippers,” says Luttrell. “We encourage intermodal where it makes sense.”

What’s Developing at Watson

The growth of intermodal transportation has outpaced the infrastructure investment required to support it. One value proposition of Watson Land Company, based in Carson, Calif., is that it has been steadily making strategic investments to support intermodal’s growing popularity with shippers.

Watson Land Company, which recently celebrated its centennial, develops, owns, and manages industrial properties throughout southern California. Watson Land Company has developed several million square feet of master-planned centers within four miles of the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach, and maintains a footprint that includes facilities in Carson/Rancho Dominguez, Chino, Apple Valley, Fontana, and Redlands, Calif.

The company recently leased a 553,963-square-foot industrial property to M. Block & Sons in Redlands. The building is a part of Watson Land Company’s Legacy Building Series, an initiative to develop and offer highly flexible, Class-A industrial facilities with distinctive architectural detail. The property will be used for warehousing, distribution, and managing third-party logistics.

Watson Land Company’s legacy extends back two centuries to the Rancho San Pedro Spanish Land Grant. Today, the company is among the largest industrial developers in the nation.

Watson holds a Foreign Trade Zone (FTZ) designation on more than eight million square feet of its distribution buildings. The FTZ designation allows customers to significantly reduce operating costs through such methods as single weekly entry of containers, which reduces merchandise processing fees and duty deferral.

Watson Land Company affirmed its commitment to sustainable design by becoming the first developer in southern California to design and construct speculative buildings in accordance with the U.S. Green Building Council’s Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) guidelines.

Each LEED-certified building features design elements, materials, functionality, and construction procedures that reduce environmental impact, enhance energy efficiency, and reduce operating costs. Watson Land Company has completed construction on more than two million square feet of speculative industrial buildings designed for LEED certification.