Send It Back! How to Manage E-Commerce Returns

Up to 30 percent of e-commerce orders shipped to customers wind up coming back. Here’s how smart retailers box up their reverse logistics strategies.

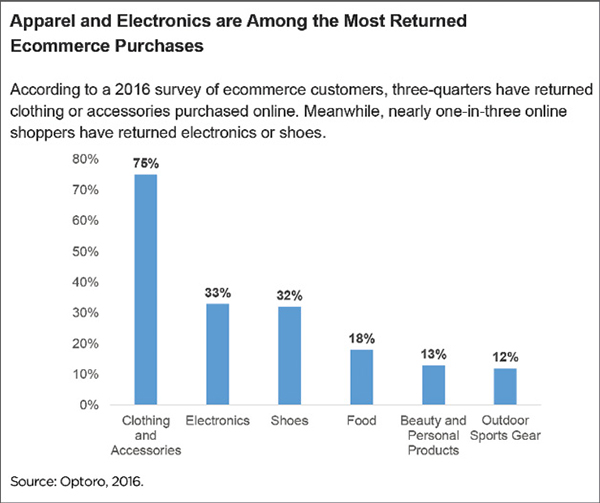

Buy something online, and there’s more than a one-in-four chance you’ll send it back. Consumers who use e-commerce return their purchases 25 to 30 percent of the time, says a study by the Office of the Inspector General (OIG) at the U.S. Postal Service (USPS). For brick-and-mortar stores, the return rate is just 9 percent.

Those figures should come as no surprise. After all, when you buy online you often take a leap of faith, hoping the sweater will look as good on you as on the model, or the headphones will provide rich, natural sound.

Increasingly, online merchants offer simple, free returns to win consumers’ trust, says Ian Stanford, a public policy analyst at the USPS OIG and co-author of the study, Riding the Returns Wave: Reverse Logistics and the U.S. Postal Service.

"How a retailer handles returns becomes almost as big a piece of its value to the end consumer as the product and the initial sales experience," says Chris Miller, vice president of logistics at San Francisco-based Narvar, which offers an e-commerce customer service software platform.

As retailers woo customers with friendly policies, returns have gained a greater role in the cost equation for e-commerce retail. "Some of the data we collected says that 20 or 30 years ago, returns were 3 to 4 percent of costs," Stanford says. "Now they’re 5 to 8 percent."

Returning the Product, Preserving the Revenue

Such changes are forcing retailers to develop new strategies for returns and reverse logistics, says Jim Brill, corporate marketing manager, returns and reverse logistics at UPS in Atlanta. Those strategies aim to make the processes more efficient, protect retailers’ brands, improve the consumer’s experience, and dispose of the merchandise—through resale or liquidation—to preserve as much of the original revenue as possible.

"Unfortunately, dealing with returns comes nowhere near a core competency," Brill says. So retailers struggle to achieve each of those goals. "Most focus on the consumer experience but are inefficient at the physical process and the disposition activities," he says.

On the customer side, retailers’ strategies often emphasize convenience and choice.

"Our brand has been built on our relationship with our customers, and we heard loud and clear from them that they wanted easier options for returns," says Mary Orrell, director of customer experience and operations at Eloquii, a vendor of plus-sized women’s fashions, based in Columbus, Ohio, and New York City.

An Eloquii customer who needs to return an item has several options: use a pre-paid shipping label to mail it back for $7; visit an Eloquii store to return it at no cost; or visit one of the 120 Return Bars currently operated in 18 metro areas by a company called Happy Returns.

Belly Up to the Return Bar

At a Return Bar, a customer of Eloquii or another participating retailer can bring items back with neither a shipping box nor label. The "Returnista" at the bar asks a few questions, examines the product to make sure it’s in returnable condition, and uses an iPad app to complete the transaction. "Within a standard credit card processing time of two or three days, customers will see the refund posted to their account," says David Sobie, co-founder and CEO of Happy Returns in Santa Monica, Calif.

The Returnista seals each item in a plastic bag and scans a quick response (QR) code on the bag to link the transaction data with the physical product. Later, the Returnista puts all the product bound for each merchant in a single box and ships it via UPS to a regional Happy Returns hub for back-end processing.

Happy Returns operates Return Bars in shopping malls, independent boutiques, and some national chains, including Paper Source stores in Los Angeles and Chicago. The company aims to expand to a total of 220 stores in 35 or 40 metros by the end of 2018, Sobie says.

Besides third parties such as Happy Returns, some retailers and carriers also have introduced new returns options. In some markets, for instance, Amazon customers can drop certain boxed-up returns in the same self-service Amazon Lockers where customers retrieve deliveries. FedEx and UPS also have established neighborhood drop-off locations in chain stores and local businesses.

As much as they value convenient drop-off options, consumers also love fast refunds. "Our statistics show that 69 percent of the end consumers will go back again and again to a company that offers a refund as soon as they return a package," says Miller at Narvar.

Customers who ship product back may wait days or weeks for the merchant to receive the product, verify its condition, and process the refund. In-person returns offer quicker satisfaction. Eloquii’s customers who use Return Bars or return to a store (where associates also use the Happy Returns app) see their refunds within one business day. "If they mail it back, it takes two to three weeks," Orrell says.

Back-End Logistics

While front-end strategies focus on delighting customers, back-end reverse logistics processes focus on increasing efficiency, cutting costs, and optimizing the value of the returned product.

What happens to a product once a customer returns it is a complex question. "In general, goods may: return to inventory; require repair, rework, or repackaging; return to the vendor; be sold on the company or vendor marketplace site as new or ‘like new’ goods; be liquidated to secondary markets; be donated to charity; be destroyed; or be discarded," says Brill.

As they decide on the disposition of products, one challenge e-commerce companies face stems from the unpredictable nature of returns. "You don’t know how much product is coming back, what’s coming back, or what condition it’s in," says Stanford. All those factors influence how product flows through the reverse supply chain.

Unpredictable return volumes can cause particular challenges for smaller e-commerce companies. "Because their volume is relatively low, small changes in the volume coming back on any given day can affect their staffing decisions," says Jacob Thomases, a public policy analyst and Stanford’s co-author on the USPS study. The more data about returns those retailers receive in advance—perhaps from carriers accepting packages from consumers—the more effectively they can staff their facilities, he adds.

The path that returned products follow through the reverse logistics pipeline may vary according to several factors. For instance, if a product is popular and a customer returns it early in the holiday shopping season, the merchant might direct it to a fulfillment center for resale. In January, that same product might go to a third party for liquidation.

Driving Retailer Efficiencies

Narvar’s platform lets a retailer change its business rules as needed. So when a customer goes online to initiate a return, the system prints the right label, sending the package to a fulfillment center, a returns processing center, a third party, or another appropriate facility, depending on the product and season. "This drives efficiencies for the retailers in terms of inventory turns and cash flow," Miller says.

Eloquii puts most of its returned items back into inventory. At the Happy Returns hub, employees return items to pristine condition—perhaps giving them a light steaming or removing stray hairs—and then repackage them and ship them to the merchant’s third-party logistics (3PL) provider.

But for many e-commerce merchants, liquidation is the more likely option.

The portion of returns that companies can resell varies with company policy, the time of year, the geographic location and other factors, but overall, the percentage is small.

"I’d say that 50 to 90 percent of it doesn’t go back for resale," says Eric Moriarty, vice president of marketplaces for B-Stock, a company in Belmont, California, that operates liquidation markets for e-commerce retailers.

B-Stock operates online marketplaces where companies liquidate returned and excess inventory, letting merchants sell directly to buyers, rather than to jobbers or other middlemen. B-Stock’s clients include major retailers such as Amazon, Walmart, Target, Costco, and Macy’s.

By cutting out the middleman, and by selling products in category-specific lots—one listing for women’s apparel and another for housewares, for instance—B-Stock brings in much more money on liquidation sales than companies could on their own, Moriarty says.

B-Stock offers transportation and warehousing through a partnership with 3PL C.H. Robinson. Retailers that use this service don’t need to crowd their own facilities with product awaiting liquidation, Moriarty says. So companies don’t feel pressure to liquidate for pennies on the dollar just to free up space.

Mixing It Up

Robert Iaria, director, last mile services at C.H. Robinson in Eden Prairie, Minnesota, points to one B-Stock/Robinson client that puts returned merchandise on mixed pallets almost as soon as it arrives in a return center, then loads the pallets onto trailers the 3PL provides.

"We pull the pallets off the site and bring them to a nearby location, where the truckloads are broken down into various-sized lots," Iaria says. B-Stock works with the retailer to develop lots for sale, and C.H. Robinson builds pallets accordingly.

When the merchandise hits the retailer’s marketplace, an application programming interface (API) from C.H. Robinson calculates the transportation cost for each lot, tailored to each bidder’s location. Finally, C.H. Robinson manages transportation to the buyer.

These are just a few solutions that retailers and their service partners have devised to help manage a flood of e-returns that is likely to grow even more intense as e-commerce captures even more market share in retail.