Global Logistics—August 2014

Only the Good Drive Young

With all the talk about the U.S. driver shortage, it’s easy to forget that similar labor constraints exist elsewhere around the world. For example, recruiting younger people into the trucking industry has become a challenge in the United Kingdom, according to Barriers to Youth Employment in the Freight Transport Sector, a report by a UK Parliamentary group. The research finds that only two percent of all heavy goods vehicle (HGV) drivers are younger than 25 years of age, while 60 percent are older than 45.

“It is also striking that there are slightly more managing directors in transport and distribution businesses who are under the age of 25 than there are HGV divers, which shows the number of barriers to getting young people driving,” says Rob Flello, a Stoke-on-Trent member of parliament.

The group pins the driver shortage on society’s lack of awareness, and government’s failure to promote vocational education. “Logistics is too often considered a job of last resort,” notes the report. “By pursuing this agenda, and highlighting universities as markers for education quality, government may have devalued skills that are crucial to the economy.”

U.S., Cuba Ride Trade Winds

President Obama’s recent Cuba directive is likely to shake up trade ties between the two countries—or at least fuel speculation. Landmark talks, which began in January 2015, may bring a resolution to more than 50 years of economic sanctions and a well-documented trade embargo against President Fidel Castro’s communist regime.

The talks are just that—a first step that could open the door to further negotiations, and perhaps a more normalized relationship between the two countries. From a trade perspective, “that’s a good thing,” says Jay Brickman, vice president government services and Cuba service for steamship line Crowley Maritime.

Crowley has been serving the Cuba market weekly for 14 years. Historically, the Office of Foreign Assets Control and Department of Commerce have authorized special waivers for transporting goods to Cuba. Much of what moves southbound is agricultural in nature.

“With the exception of a few items, all northbound shipments to the United States are prohibited,” says Brickman. But this could change. And it couldn’t be happening at a better time for Cuba.

The country’s reckoning as a transshipment hub has been a focal point, thanks in large part to Brazil, which is helping to bankroll a $1-billion overhaul at the Port of Mariel. Situated 30 miles west of Havana, the new complex can handle 800,000 TEUs annually. When dredging is complete, Mariel will be able to accommodate new Panamax vessels transiting the Panama Canal.

The investment is a huge play to capture some transshipment volume expected to surge through the Caribbean region beginning in 2016. But competition is stiff. Panama, U.S. South Florida ports, Jamaica, the Dominican Republic, the Bahamas, and Colombia all have eyes on the expected cargo growth. Cuba has a lot to gain—especially if certain cards fall into place.

It’s still too early to conjecture how this most recent diplomatic dalliance will play out. Social, political, and economic reforms do not come easily or quickly. Stateside, Congress needs consensus to lift economic sanctions. But the possibility poses some intriguing questions.

Brickman doesn’t think Cuba will necessarily factor into the transshipment fray. It’s targeting about eight percent market share for the region, which is “not super ambitious,” he says. Rather, Cuba’s real opportunity lies in becoming more of a manufacturing and distribution hub.

“Cuba has created a 180-square-mile industrial development zone contiguous with the Mariel port,” Brickman says. “You’ll be able to drive directly from the port into the industrial development zone. This is different than a free trade zone because it encourages investment that can combine production for local market and for manipulation and export. This is more important for the port’s future than transshipment.”

Investments in the new zone can be wholly foreign-owned, which is drawing interest from Chinese and Brazilian companies that have a major stake in the region.

Given Cuba’s proximity to the United States, particularly South Florida’s booming consumption market—Miami is fewer than 250 miles from Havana—there’s also offshoring potential. Whether Cuba opens up to importing U.S. goods remains to be seen. But there’s plenty of incentive to grow its industrial base for exports.

“With regards to outsourcing, industries generally try to get into a place with a significant local market,” Brickman says. “Cuba has a population of 11 million people, many with low incomes. It’s not China. Nor is it like Ireland, which offers access to the common market.”

Cuba presents an interesting dilemma. There is a lot of inertia, especially dealing with an insular, socialist economy. “But Cuba is making adjustments to become more competitive and attractive,” says Brickman.

It just might take some time before that happens.

Seaway Floats On $7-Billion Investment

The Great Lakes-St. Lawrence system is one of North America’s most underappreciated transportation assets, especially when you consider that it facilitates more than $35 billion in trade, and contributes 227,000 jobs to the United States and Canadian economies. But if capital inflows are any indication, that recognition may be changing.

As reshoring activity picks up pace, the waterway’s importance connecting the heartland with global markets is once again front and center. Maritime trade consultant Martin Associates has documented how much capital is being sunk into an inland system that for many years was synonymous with the Edmund Fitzgerald.

Total investment in the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence system is approaching $6.9 billion, including capital spending on ships, ports and terminals, and waterway infrastructure, according to Martin Associates. Of that amount, $4.7 billion was invested in the navigation system between 2009 and 2013, and another $2.2 billion is committed to improvements between 2014 and 2018.

It has truly been a public-private effort, with 67 percent of funding coming from government and 33 percent from the business community. Among the notable outlays, American, Canadian, and international ship owners are spending $4 billion on the biggest renewal of the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence fleets in 30 years. The U.S. and Canadian governments have also dedicated close to $1 billion to modernize the seaway’s lock infrastructure and technology during this 10-year period. And, Great Lakes and St. Lawrence River ports and terminals are collectively investing more than $1.7 billion on expanding docks, equipment, facilities, and intermodal connections.

Such investment has not gone unnoticed by the business community. “The Great Lakes-St. Lawrence system is integral to ArcelorMittal’s steel and mining facilities in Canada and the United States as we utilize shipping for millions of tons of raw materials and finished products,” says Sean Donnelly, president and CEO of ArcelorMittal Dofasco, Canada’s largest flat-rolled steel producer. “Investments in fleet renewal, and improvements to infrastructure contribute to our business success and to the sustainability and profitability of the entire marine transport supply chain.”

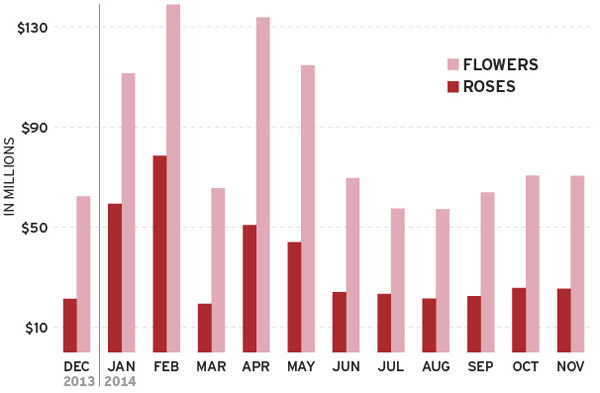

Roses Rise in February

In 2014, February flower imports (fresh cut) reached more than $138 million; about 52 percent of those were roses. Roses continue to be the number-one flower purchased in the United States, and the top Valentine’s Day bouquet.

Source: Zepol Corporation

Panama OKs New Port

Concurrent with canal expansion, Panama is starting to build out surrounding infrastructure, which will be equally important as the country looks to compete as a Latin American distribution and logistics hub.

The Panama Canal Board of Directors approved the development of a transshipment port in Panama’s Corozal region. When completed, the facility will accommodate more than five million TEUs at the canal’s Pacific entrance.

The project’s first phase features three docking positions for new Panamax ships, and a handling capacity of about three million TEUs. The new port may also grow canal tonnage, given the proximity of both facilities to one another.