The Logistics of Liquidation

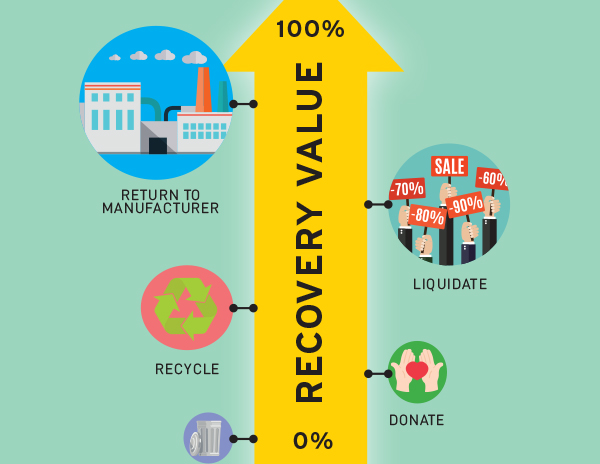

When a customer returns a product, or a company clears unsold merchandise off the shelves, that’s the start of an uphill climb in search of maximum value recovery.

It’s easy to picture retail as a river, with product flowing from manufacturer to merchant to consumer. But think about all the merchandise consumers return, including about 30% of goods sold online. Some of that product goes right back on sale, but much of it isn’t in sufficiently perfect condition. Then consider the product that never gets sold in the first place.

The last thing a company wants to do is write off this merchandise and truck it to a landfill. That’s where reverse logistics and liquidation come in.

Reverse logistics refers to the process of receiving returned or unsold merchandise and preparing it for the next step in its lifecycle. Liquidation refers to the sale of this product through secondary channels.

Those towels you examined at Ollie’s Bargain Outlet? That lot of 500 pairs of earrings on eBay? The still-in-the-box panini grills at the weekend flea market? They all got where they are thanks to liquidation.

Besides returned items, products that go into liquidation channels can include shelf pulls (merchandise that was put up for sale but never bought) and overstocks (merchandise the retailer no longer wants because it’s out of season, obsolete, or otherwise undesirable), says Renee Cyr, who together with Robert Cyr operates Product Sourcing 101, an information publisher and community for buyers and sellers of wholesale merchandise.

Products for liquidation also include salvage goods, which pose a particular challenge. “True salvage merchandise is defined as broken and/or damaged items that have been tested and deemed of little value,” Cyr says. Liquidators seek to squeeze what value they can from those items.

Three Goals

A well-conceived strategy for reverse logistics and liquidation helps a company achieve three kinds of goals, says Jeff Rechtzigel, vice president and general manager, retail at Liquidity Services, a Dallas-based company that helps customers with asset recovery, returns management, and merchandise sales.

The first goal is to recover as much value from merchandise as possible. “That recovery calculation is a combination of how much one is able to sell it for, less all the costs that go into the selling process,” he says.

The second goal is to protect the brand by handling products responsibly, and protect consumers by destroying personal data connected with electronics and other returned products.

The third goal is to uphold a company’s sustainability principles. “Unless something is completely broken, there is a buying market for it,” Rechtzigel says. “Even if the net recovery on a product is low, it’s better not to have it end up in a landfill.”

For a company trying to recover value from returned merchandise, the first step is to sort those miscellaneous items and determine what to do with each. For example, Ryder Supply Chain Solutions, based in Miami, operates a site in Pennsylvania for a large telecommunications company, where it processes used equipment that consumers return, such as set-top cable boxes and Wi-Fi routers.

“We screen that product to see whether it still works and can be put back on the shelf,” says Norm Brouillette, vice president of operations at Ryder Supply Chain Solutions. Employees at the site clean each unit to remove contaminants such as dust and insects.

If it’s in good enough shape, they put the item back in stock to be resold or re-rented. If the unit doesn’t work, technicians repair it. If the company doesn’t want to reuse a unit, Ryder sells it for scrap. “We certify that it was not put in the landfill or sent somewhere as trash,” he says.

Asset Recovery

In its asset recovery service, Liquidity Services also prepares returned items for resale, either in the original market or through secondary channels. “Those services can range from simply removing labels and marks from products, to repackaging, to data wiping to delete any consumer data that may be on electronics, to refurbishment, rekitting, all the way through detailed repair,” Rechtzigel says.

Bulldog Liquidators, a retail liquidation chain headquartered in the Los Angeles area, does its own processing. Bulldog buys overstocks from retailers, wholesalers, and other sources and sells that product to the public for 40% to 80% off the retail price. When it strikes a deal with a seller, Bulldog sends one of its own trucks or a carrier’s truck to transport the merchandise to one of its warehouses across the United States. There, workers examine each item.

“We have to make sure it’s working, tested, and complete,” says Steve Pazmany, Bulldog’s vice president of retail. “If it’s a used product, it has to be cleaned and tested. If it’s a brand new product, that’s amazing.” When Bulldog can’t get a product working, it may sell it for parts—for example, selling a broken vacuum cleaner to a vacuum repair shop.

Choosing the Channel

Once a seller or its third-party partner sorts and prepares merchandise for liquidation, it’s time to send the goods into a sales channel. This often poses an interesting challenge. “Often entire loads, pallets, or lots are mixed goods, which will not sell through any one platform,” says Cyr. “It’s common to resell goods using multiple resell channels.”

Larger, bulkier items may sell through local sales applications such as OfferUp, Letgo, or the Facebook marketplace. “Name-brand merchandise works extremely well on platforms such as Amazon and eBay,” Cyr says. “Lower-value items are typically sold through discount bins in brick-and mortar stores, in flea markets, and/or a local auction.”

Bulldog’s main sales channel is its chain of 10 brick-and-mortar stores in five states. But thanks to its 30-day return policy, the liquidation retailer also sells merchandise into other liquidation markets. “When items that we sold come back, they get palletized and we sell that pallet,” Pazmany says. Buyers are likely to be people who sell at garage sales and swap meets. Bulldog also liquidates product that has been sitting in its stores too long, to clear space for fresh merchandise.

Liquidity Services provides three sales channels. One is Secondipity, a direct-to-consumer platform for refurbished consumer electronics.

The second is Liquidation.com, an online platform for business-to-business sales, where millions of registered users buy bulk lots ranging from a box full of product to a truckload. “They are typically using that product for some form of resale, in their own stores or flea markets, or in a repair operation,” Rechtzigel says.

The third channel is for larger customers. “It could be many truckloads of product shipping to a large retailer or truckloads or containerloads of product exporting to another country,” Rechtzigel says.

Product Sourcing 101 also offers an online marketplace for liquidated goods, as do many other service providers.

Among the challenges that companies face in the liquidation process, an important one is sorting the mixed products that come back in all different conditions.

“It’s not a clean business,” observes Brouillette. “Retailers that are selling the product may not want to have that come back into the primary hub.” The retailer might rather have a third-party partner such as Ryder take this product into one of its own facilities for processing.

Through its information technology, Ryder keeps customers up to date on the status of all their products going through the reverse logistics process. “We can show them that it has been returned and what the status of that return is,” Brouillette says. “Has it been put back in stock? Will it need to be repaired?”

For companies on the buying end, liquidated goods pose another sort of challenge: Often, buyers have to commit to a purchase sight unseen or without a manifest. “Sourcing liquidation goods can, at times, be described as gambling,” says Cyr. Buyers should be careful not to let the excitement of the gamble overrule their best instincts.

“Learn as much as possible prior to sourcing distressed merchandise,” Cyr recommends. “Use common sense in all regards. If a deal sounds too good to be true, follow your gut.”

Recommerce: What’s in a Name?

If you’ve been reading up on reverse logistics, you may have run across the term “recommerce.” And you may have discovered contradictory definitions.

Jeff Rechtzigel, vice president and general manager of retail at Liquidity Services in Dallas, defines recommerce as performing value-added activities on returned or excess products and reselling them in a way that gains the highest possible net recovery, protects the brand, and is environmentally sustainable.

“What’s cool is that recommerce can happen on the original retailer’s or manufacturer’s store or website,” Rechtzigel says. For example, an item purchased from Walmart and then returned could end up for sale on Walmart.com through a third-party merchant.

For some, recommerce refers to used products—especially electronics—that consumers trade for cash to companies that refurbish and resell them. A similar concept exists in the fashion world, where consumers may sell used clothing to resale companies such as thredUP and The RealReal, or brand owners may establish resale programs of their own.

However you define it, recommerce represents part of a larger movement to eliminate waste in the reverse supply chain and give products a new lease on life.