It’s Only Natural: The Challenges of Organic Food Logistics

From cold chain and cross contamination to scale, organic farmers are addressing challenges with technology and supply chain shifts.

Most farmers, food distributors, and grocers have daunting challenges on their plates, including tight margins, unpredictable trade wars, and perishable products that require an impeccable cold chain and precise transportation schedules. Those who farm or work with organically grown produce, dairy, and meat can add a few more challenges to the menu: potential cross-contamination from conventionally grown foods and competition from criminals seeking the premiums organic foods typically enjoy, without actually doing the work required to claim their foods are organic.

In addition, many—although certainly not all—organic farmers run small businesses, making it difficult to achieve economies of scale in their transportation, cold chain, and distribution efforts.

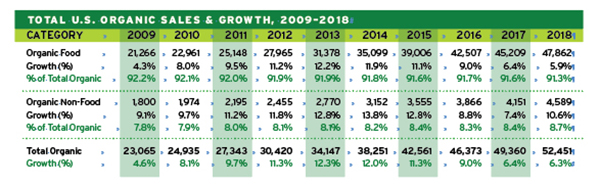

Organic farmers, distributors, and grocers are tackling these challenges through technological advances and supply chain enhancements. These efforts are increasingly critical, given the rising demand for organic food. Consumption of organic food topped $47 billion in 2018, up almost 6%, reports the Organic Trade Association (OTA). That compares to an increase of 2.3% for total food sales. Organic foods, which are grown without the use of toxic and/or synthetic fertilizers, antibiotics, artificial preservatives, flavors, and colors, now account for 5.7% of all food sold in the United States, says the OTA.

Because organic foods don’t contain many of the preservatives found in conventionally grown foods, some are even more perishable. "Organic foods cannot have any breakages in the cold chain links," says Patrick Penfield, a professor of supply chain management at Syracuse University.

Cold Chain Tech

Technology can help. A growing array of sensors that monitor temperature, as well as shipment location, transit time, and other metrics during transportation continue to drop in cost. "The costs are decreasing, putting this technology within reach for many shippers," says Brian Nessel, vice president of operations with GlobalTranz, a third-party logistics provider based in Scottsdale, Arizona.

Organically Grown, a distributor of organic produce based in Eugene, Oregon, requires all its carriers to pre-cool their trailers before making pick-ups. Organically Grown also uses temperature loggers to continually track temperatures once its food is on a truck.

During deliveries, dock seals—large pads the trailer backs up to—form a seal between the building and truck, keeping pests and debris out while keeping the cold in. "There’s zero break in the cold chain," says Anthony Seran, logistics coordinator for Organically Grown.

Organically Grown also is considering using permanently mounted thermometers within its trucks that will report temperature readings through the cellular network. "This takes GPS a step further," Seran says. In addition, it would reduce the need to recycle the temperature sensors currently used.

Within temperature-controlled warehouses, energy and labor are the largest costs. "Many cold storage companies are investing in automation that enables more efficient labor usage," says Corey Rosenbusch, president and chief executive officer with industry group Global Cold Chain Alliance.

One company is altering actual cold chain technology. Phononic uses semiconductor chips, rather than compressors, to remove heat from a cavity. "The end result is the same as a compressor," says Abhiroop Dutta, director, product management, food and beverage, with the Durham, North Carolina-based company. However, Phononic’s chip-based technology eliminates the coils needed with conventional cooling systems, resulting in a smaller, lighter refrigeration unit.

Co-mingling & Contamination

The careful handling required for many food items becomes even more important with organic food, which requires extra TLC. In part, that’s because the lack of preservatives can make it more perishable.

In addition, organic food producers need to watch for contamination and commingling. Contamination occurs when organic food comes into contact with prohibited substances, such as a pesticide. Commingling occurs when organic foods come into contact with non-organic products.

The USDA has identified practices that can reduce the risk of commingling and are approved for organic foods. One is buffer strips, or plots of land located along the edges of fields that can capture pesticides and pollens, perhaps from neighboring farms. In addition, clearly labeling organic ingredients or foods can help prevent accidental commingling.

While these practices help to maintain the integrity of the organic supply chain, they also add to its expense and complexity. That can be a challenge for organic growers, as their farms tend to be smaller than conventional farms.

Fighting Fraud

Organic farmers must face the small percentage of competitors who want to capture the price premiums organic foods typically enjoy without actually following organic growing regulations.

While much of the fraud originates outside the United States, domestic cases aren’t unheard of. For instance, in August 2019, Randy Constant, a Missouri farmer convicted of marketing non-organic soybeans and corn as organic—a case some called "Field of Schemes"—committed suicide several weeks before he was scheduled to begin his jail sentence.

Eric Jackson, founder and chair of Pipeline Foods, which offers supply chain solutions for farmers of organic products, says his organization invests time and resources to ensure its products are organic.

For example, Pipeline uses "mass balance analysis" to confirm each purchase is organic. Say a farm is growing 10 acres of organic corn, and each acre likely will produce about 150 bushels. If Pipeline commits to purchasing the output of those 10 acres, it should wind up with about 1,500 bushels. If a farmer offers another 1,000 bushels, Pipeline will "have to understand clearly how they were grown before committing to them," Jackson says.

Pipeline’s farmers also are independently audited and Pipeline tests all incoming loads for GMOs. Agreements with all its growers allow Pipeline to test their soil at any time. "It’s expensive to do what we do," Jackson notes.

The Organic Trade Association also has established a fraud prevention program for developing a robust supplier approval program, conducting internal audits, and understanding the length and complexity of the supply chain.

SOURCE: ORGANIC TRADE ASSOCIATION’S 2019 ORGANIC INDUSTRY SURVEY CONDUCTED 1/25/2019—3/26/2019 (CONSUMER SALES).

Scale

The average organic farm comprises 285 acres, versus 444 acres for all farms, according to Modern Farmer. The generally smaller scale of many organic farms can make it harder for them to invest in technology. That can reverberate throughout a supply chain.

For instance, HighJump, a supply chain management solutions provider, works with a wine distributor that has several clients who have yet to implement barcodes. “There is some automation but also manual processes to deal with,” says COO Joe Couto.

Some distributors offer services aimed at helping organic farmers gain economies of scale so they can operate more efficiently. Co-op Partners Warehouse (CPW), an organic wholesale distributor, provides transportation for goods from more than 30 local farms to about 400 customers.

For its services, CPW charges a handling fee, while also encouraging its farmer customers to maintain direct relationships with their customers, such as restaurants and stores. “They get higher prices selling directly to the retailer,” yet don’t have to manage logistics, says Rick Christianson, purchasing manager and produce buyer.

While many in the industry were initially skeptical of CPW’s approach, “It’s unique and has worked well for us,” Christianson says.

Organic Valley, a cooperative of more than 3,000 farms based in La Farge, Wisconsin, established Organic Logistics (OL) to provide efficient transportation and storage of its own products, as well as products from other small producers. “Not many carriers specialize in smaller LTL shipments that can capitalize on the transit and routes they are already servicing,” says Milo Luppen, OL vice president.

Organic Logistics consolidates products from Organic Valley and other producers. It’s able to fill its trucks and warehouses while also providing systems and services, including inventory management, fulfillment, and shipping to “smaller companies who don’t have the resources to effectively utilize the chain of supply,” Luppen adds.

While not exclusive to organic farmers, food hubs can help small and mid-sized farmers broaden their distribution networks and customer bases. Food hubs “offer a combination of aggregation, distribution, and marketing services at an affordable price,” according to the USDA.

Some offer kitchen facilities, so farmers can create value-added products from the food items they grow. Other services can include transportation, warehousing, and cold storage, all of which can make it possible for small producers to access larger markets.

Looking Ahead

Some see blockchain as a potential solution to combat organic food fraud, as it can provide tamper-proof records showing how organic food items were handled. However, many believe it will be some time before it’s fully adopted. "It takes time for technology to make its way through the supply chain ecosystem," says Derek Curtis, vice president of sales and retail execution, HighJump.

One challenge that many in the organic industry welcome is its increasing popularity. "Demand is exceeding supply," says Anthony Seran of Organically Grown. As a result, he often needs to schedule pickups from the same producer several times each week.

This shift also highlights one benefit of working with numerous smaller growers: it increases the likelihood that Seran will be able to assemble both the quantity and variety Organically Grown customers have come to expect. "We get greater access to supply and variety," he says.

The growing popularity of organic food also means more growers and distributors will need organic warehouse and cold chain facilities. "Organic will go from a differentiator to a market standard," predicts Corey Rosenbusch of the Global Cold Chain Alliance.